Even if you aren’t familiar with Keith Haring, you will almost certainly be familiar with his art. Works like Radiant Baby have been seen everywhere from the Berlin Wall to Sesame Street. Haring’s simple, punchy line drawings of cartoon-like figures were made to have universal appeal. The kinetic characters, combined with the bold and vibrant colours of street graffiti, created an unambiguous visual language perfectly suited for the communication of social and political messages. Haring is rightfully remembered for his commitment to creating art for the public, which he expressed in his famous motto: “Art is for everybody.”

Keith Haring’s commitment to “art for everybody” ran deep, permeating not only the style but the political content of his work. Some of Haring’s most iconic works are those which make bold calls for change, engaging with social crises like South African apartheid, Reaganism, the oppression of LGBTQ people, and the AIDS epidemic which would eventually take Haring’s own life. But today, the appropriation of Haring’s legacy by elite art auctions and ritzy brands poses an important question: under capitalism, can art really be for everyone?

Haring’s formative years in the death of the postwar boom

The art world that Haring entered into as a young man was in a period of upheaval. The postwar boom after World War II had created a massive economic upswing for the capitalist system. It produced an explosion of investment, trade, and production. With all of these new technologies, the capitalist class was forced to transform marketing to sell their commodities and distinguish themselves from the competition. Marketing firms poured enormous resources into researching the best tactics to manipulate audiences in pursuit of greater market shares.

Photo credit: Thad Zajdowicz/Flickr

The 1970s saw the rise of subliminal messaging, conspicuous consumption, and other advertising schemes. As mass marketing continued to rise through television commercials and other media, the odious concept of “commercial art” was born. Commercial art utilized blunt and in-your-face imagery to quickly communicate what a product was and why the viewer needed it. It was the first conscious attempt to use art for the express purpose of influencing viewers and selling commodities.

Haring’s art career began in 1976, just two years after a historic economic crash that heralded the end of the postwar boom and the beginning of a period of intense reaction and social crisis.

The capitalist system could no longer afford the reforms of the past. Instead, the ruling class could only offer privatization, plunder, and counter-reforms. Reagan and Thatcher, elected just a few years after the crash, were only too happy to make the working class pay for the crisis. Finally, the AIDS epidemic, which would soon permeate every aspect of Haring’s life, was only just beginning.

Haring briefly studied commercial art in Pittsburgh, as it was one of the only viable ways for artists to make a living at the time. He quickly became disillusioned with the soulless world of commercial art after two semesters. In 1978, he moved to New York to study painting. Here he was highly influenced by “pop art”, but also highly critical of it. Pop art was born from the rise of commercial art, and bore its emphasis on mass appeal rather than artistic meaning.

In New York, Haring found his personal art philosophy through the writings of Robert Henri, an American artist who opposed the elitist academic art of his day, and instead sought to capture the life of the everyday person. Henri’s philosophy revolved around the idea that “art when really understood is the province of every human being”.

This would serve as the foundation for Haring’s entire art career, and put him at odds with the approaches to art which dominated at that time. In this period of austerity and reaction, art was decidedly not the province of every human being. The investment poured into commercial and pop art was not really an investment in art at all, but an investment in corporate advertising which happened to make use of artistic elements. As the ruling class was forced to penny-pinch, artistic projects were kiboshed unless they could line somebody’s pockets. As a result, art was defined by complete surrender to commodification, or—as Haring would soon find out—complete indifference toward everyday people.

Good business makes the worst art

When Haring began studying painting and encountered the world of “high art”, he found that it was not any less profit-driven than commercial art. It just aimed at a different, more exclusive market: the ultra-wealthy, celebrities, and art dealers, rather than everyday people. In a biography, Haring describes how art-dealer “creeps” would come into his studio “trying to rip me off” and resell his work for more money. He describes the “traditional art-dealer gallery” as what he “hated about the art world”, vowing to never go with a gallery and dealer because they would “corrupt” him.

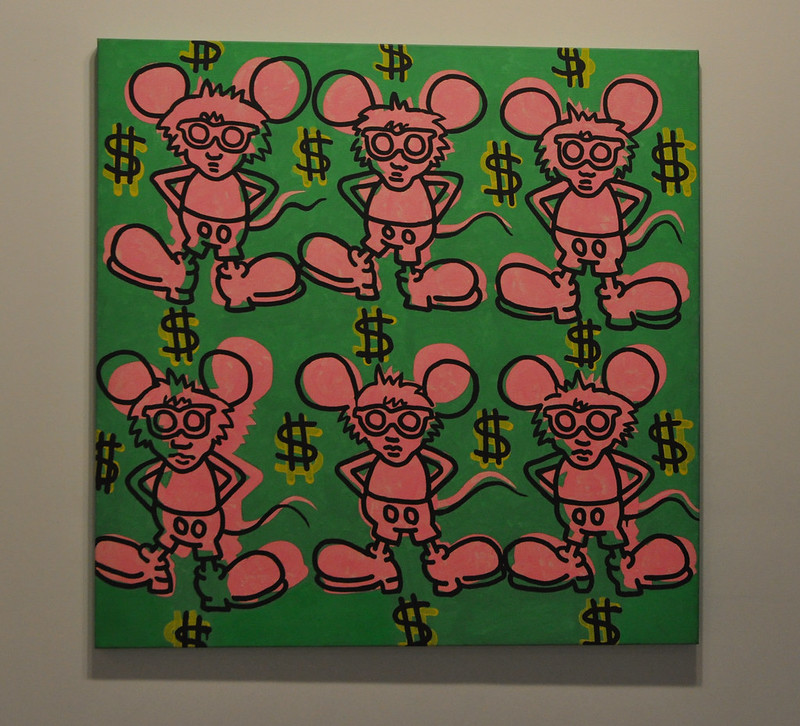

At the same time, Haring still abhorred those who paid attention to the masses only to sell them commodities. Andy Warhol, a mentor with whom Haring had a complicated relationship, accepted and embodied the complete subordination of art to the profit motive. His famous saying demonstrates this: “Making money is art. And good business is the best art.” Haring once wrote in his journal, “[Warhol] is in fact a very, very different kind of artist. Andy has been… an example of both what to be and what not to be”. Haring’s critical attitude toward Warhol’s zealous acceptance of art-for-profit was reflected in a series of works called Andy Mouse.

Haring’s most important influences while in New York came not from the elitist atmosphere of art school, but from famous graffiti artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Angel Ortiz. He was inspired by their spontaneous creations with incredible technical skill that drew the public into each piece. Graffiti had recently taken off in America at the end of the 1960s, as political activists and artists began to use their graffiti more like a personal soapbox. Worsening social conditions and increasing hardship drove more artists towards this rebellious art form. What started as simple, repetitive “tags” with names or short slogans grew into “[master]pieces”, which are large and elaborate works often taking up entire building walls, as artists aimed to build their reputation and one-up other graffiti artists. Haring would eventually paint several of his own “pieces” around the world.

Haring was in search of a similar way to reach the public as an artist without succumbing to the monstrous greed of the capitalist world, whether in the form of commercial art or the art of high-society auction houses. He described this dilemma in his first journal entry after moving to New York:

The public has a right to art.

The public is being ignored by most contemporary artists.

The public needs art, and it is the responsibility of a “self-proclaimed artist” to realize the public needs art, and not to make bourgeois art for the few and ignore the masses.

Art is for everybody…

Art can be a positive influence on a society…

Art can be a destructive element and an aid to the takeover of the “mass-identity” society.

The style worked out by Haring expressed his philosophy toward art. It combined the accessible “pop” style with the artistic spirit and medium of street art and graffiti. With this, Haring would soon debut himself to the world.

Elvis must be Elvis: From the subway to the galleries

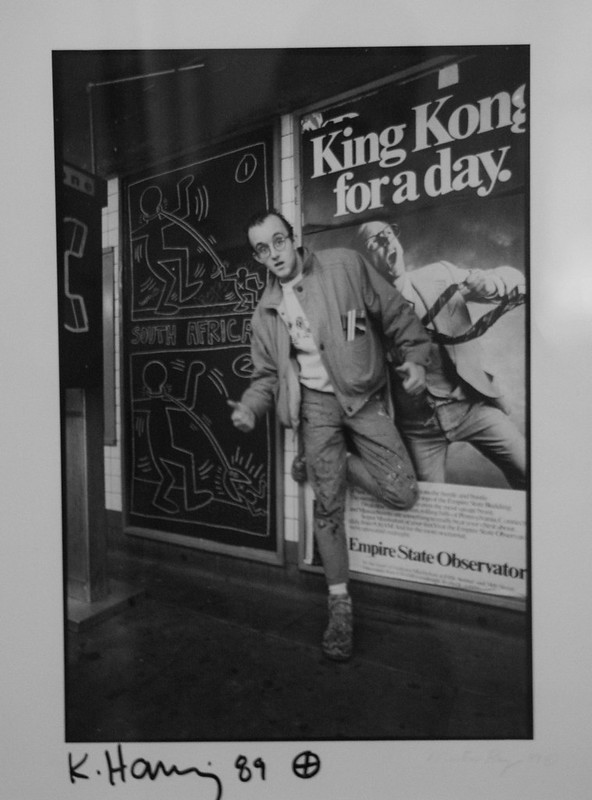

Like millions of other New Yorkers, Haring spent much of his time on the subway. It was here where Haring would create his first works of art for the public in 1980. On his long subway rides, he encountered empty black panels of paper that covered expired advertisements. Armed with chalk, he made simple drawings that would serve as the foundation for the art style he is famous for today.

Everywhere Haring went, he found that people were awestruck by the chalk drawings. Crowds would often gather while he drew, hoping to find out what the artist was trying to say, and why he was saying it. Haring thrived in this environment. In his journal, he described these drawings as “my contribution to the world. I will draw as much as I can for as many people as I can for as long as I can. Drawing is still basically the same as it has been since prehistoric times.

It brings together man and the world.”

According to Haring, the chalk drawings were inspired by pop culture to be “universally readable” to prompt people to think about the world, technology, and events happening around them. His aim was not to tell people what to think, but rather to encourage them to take in and interpret the drawings on their own. The finer details and message were left to the imagination.

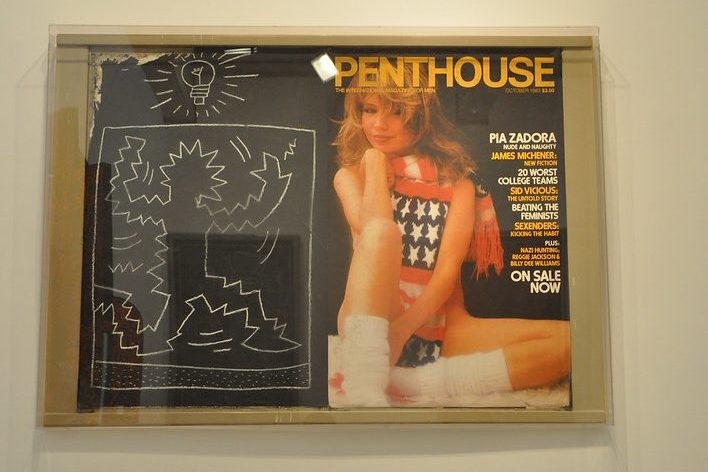

The juxtaposition of Haring’s drawings provoking the viewer to think and enjoy, appearing beside advertisements, was no accident. Haring’s art was a clear revolt against the invasive blight of advertising on every aspect of our world. It was a chance for people to break away from this constant barrage of advertisements. Where everything around Haring said “do this” or “buy that”, Haring replied with his art, “Enjoy and think what you will.”

Haring’s drawings were not just a means to express himself, but an open declaration of the responsibility Haring felt to create art for the public. He was able to provide them with opportunities for reflection and aesthetic enjoyment, not just advertising. This is a valuable and rare experience for everyday people.

The average worker is not afforded the ability to visit the upscale art galleries that the revolutionary Leon Trotsky called “concentration camps of the mind”. What Trotsky means is that this wealth of culture and creativity is deliberately locked away from the people, where only the wealthiest can afford to open the doors. For the rest of us, we are left with crumbs of culture and a bare existence.

Haring’s subway art is an attempt to overcome this contradiction. Since people couldn’t be brought to art, he brought his art to the people. However, Haring quickly ran headfirst into the barriers of the capitalist system. The hundreds of drawings he created, sometimes more than forty pieces per day, got him arrested and fined for “defacing public property” and “vandalism” hundreds of times.

Thankfully, Haring was able to use his connections from art school to exhibit his art at nightclubs and other spaces—but this stroke of fortune reminds us how many artists could not have done what Haring did, even if they possessed the same amount of talent. If an artist cannot afford to go to art school, forge advantageous connections, pay expensive rents in galleries, and so on, then they cannot share their art with the public. We know of Haring’s art today not simply because the society he lived in recognized his merit, but because he was able to navigate past the barriers posed by it.

Eventually, Haring’s art was shown in exhibitions around America and Europe, gaining him international recognition. He rubbed shoulders with world-famous celebrities and artists, including Madonna and Vivienne Westwood. This growing recognition brought numerous lucrative opportunities that enabled him to survive on his art alone. He even went on to work for Absolut Vodka, MTV, and the United Nations.

However, in creating art for others as a career, he was exposed to a great deal of pressure to abandon the entire reason he had started creating art. How could he create “art for everybody” while crushed by corporate interests and the drive to maximize profits? He feared this pressure from the beginning of his fame. In 1982, Haring wrote, “In one year my art has taken me to Europe and propelled me into a kind of limelight. Things tend to get over-hyped and then consumed and placed into… history. I do admit in some ways this does frighten me, but on the other hand, what is the alternative? Elvis must be Elvis.”

Despite Haring’s longstanding personal disdain for art galleries and collectors, his fame brought unavoidable contact with the financial pests of the art world. In an interview toward the end of his life, he was asked a loaded question: “What happened to your resolve to stay away from the traditional, snobbish art scene?” Haring replied that eventually he became exhausted by tire kickers, and simply wanted to paint full-time. He explained, “I wanted to sell paintings because it would enable me to quit my job.” The sheer amount of work involved in meeting potential buyers was keeping him from his own art.

Ultimately, Haring was forced into line not because of his own choices, but because of the economic reality of being an artist under capitalism. He had no choice but to sign with a dealer and sell his art if he wanted to be a successful artist. The commodification of Haring’s art was already well underway before ever signing with a dealer, and refusing to do so likely wouldn’t have changed that. His personal distaste for dealers, galleries, and the commodification of art was no match for the capitalist market, for which nothing is sacred and everything has a price.

His fame also led to the decline and eventual end of his beloved subway art. By 1986, they were taken down to be sold as quickly as he could put them up. All of this came to be because, in Haring’s words, “Elvis must be Elvis.”

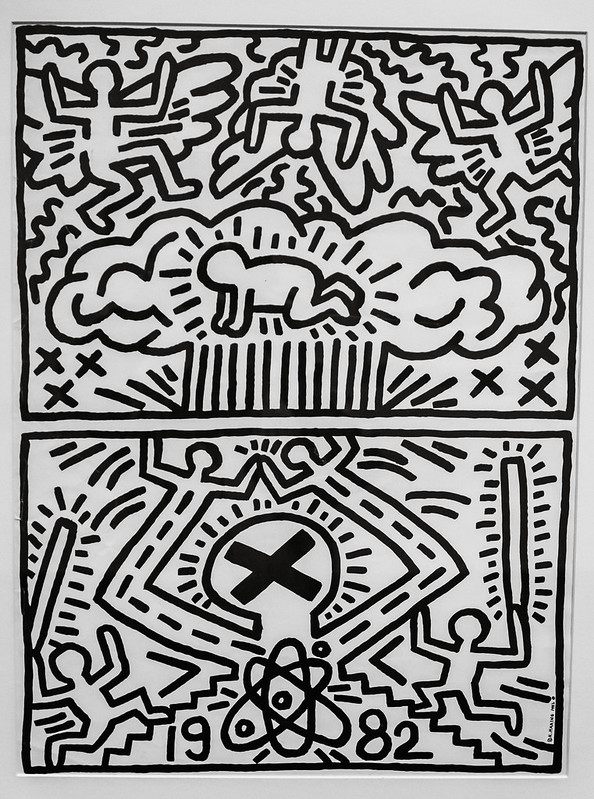

At the same time, Haring was becoming more and more politically active as he was shaped by the events around him. His first artistic foray into politics was via the anti-apartheid movement. The anti-apartheid movement in the U.S.A. had been building for years by the time Haring became politically conscious. The 1970s and ’80s saw a large upswing against South African apartheid in the U.S. Spurred on by the Soweto uprising in South Africa, where Black students protested against mandatory school instruction in Afrikaans, a solidarity movement extended to America over the next decade. In 1985, Haring created several paintings and drawings in his characteristic style arguing for the end of apartheid with the Free South Africa coalition. His posters frequently showed Black characters retaliating against the white characters enslaving and restraining them. Clearly, Haring saw his art as a way to aid the fight of the oppressed and give expression to their struggle, especially at the height of his fame.

Haring also began creating art that was intentionally provocative, forcing the audience to consider difficult and taboo subjects. The most famous of these was his work about safe sex and homosexuality. Penises, homoerotic imagery, and sexuality in general became staples within his work. He hoped to bring discussion of “forbidden” topics out into the open. This bold artistic goading was the preparatory work for Haring’s political art by which he hoped to accomplish the same task.

The Pop Shop

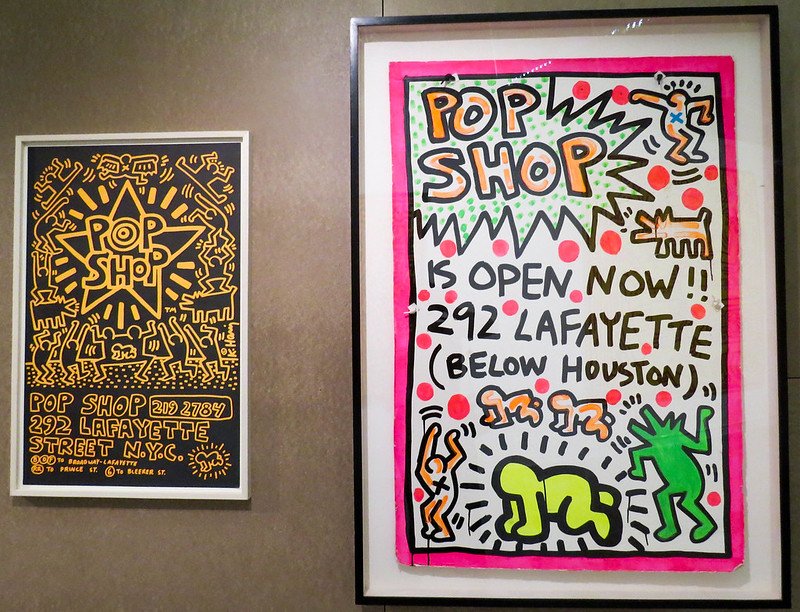

The height of Haring’s fame while he was alive came from an initiative called the Pop Shop. The Pop Shop was a store opened in 1986 where Haring began selling his art as buttons, clothing, and other memorabilia. In an interview about its opening, he gave two reasons for creating the store. The first reason, a childhood dream; the second, “There were so many copies of my stuff around that I felt I had to do something myself so people would at least know what the real ones look like.” According to Haring, the Pop Shop provided his version of “fast food, or fast art”.

Here we are given the clearest insight into what “art for everybody” means under capitalism: owning your own business and selling your art as commodities! Haring’s philosophy for opening the store stemmed from a desire to make his art more affordable to the public, since his art was skyrocketing in value. Unfortunately, if Haring wanted to make his art “for everybody”, he was forced to commodify it: $20 T-shirts, $250 gold babies, and $350 embroidered satin jackets were what the shoppers could look forward to. While he apparently aimed to keep prices as low as possible, it does not change the fact that many of his admirers could not afford to own these items. At the same time, many artists criticized Haring for commodifying his work and “selling out”, as they felt he should either create exclusive, expensive items, or stay down in the subway all day!

The Pop Shop’s items were artistic expressions of Haring’s through and through. Every item was meant to be an art piece, not just something to be sold. He wanted to attract the same wide range of people who had been drawn to his subway art, and described the inflatable babies, T-shirts and other items as “wearable print–art objects”. He wanted to produce things for everyone without “cheapening the art”, so it was still an “art statement”.

Haring was trapped between a rock and a hard place due to the conditions of capitalism. If Haring had remained in the exclusive upper echelons of the art world, his art would only be seen by art dealers and the ultra-wealthy. On the other hand, guerilla-style subway art and political posters didn’t allow Haring to reach the masses in a reliable, large-scale way. The Pop Shop represented Haring’s attempt to make his art more readily available to the public—but it also necessitated a business model that, ironically, generally made his art too expensive to attain for poor and working class people. And even this was not sustainable.

Final years and the AIDS epidemic

The final years of Haring’s life brought his most outspoken political activism, as he was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 1988. HIV and AIDS had haunted Haring and the gay community for decades by that point. The Reagan government’s conscious refusal to respond to the epidemic marks one of the most barbaric expressions of this overall period of capitalist reaction. Two years before Haring was diagnosed, he wrote in a 1986 journal entry that “the main reason I am writing is the fear of death… I saw my friend Martin, I saw death. He says he has been tested and cleared of AIDS, but when I looked at him I saw death.”

A year later in 1987, Haring attended an art show that emphasized the immortality of art. In his journal from that day, Haring said that this struck a deep note inside him, because “I am quite aware of the chance that I have or will have AIDS.” This fear was no doubt exacerbated by the fact that capitalist politicians promoted panic and moral outrage about AIDS while completely failing to help those affected by it.

LGBTQ people were blamed by the media for “the gay plague”, while incorrectly reporting that it could be contracted through toilet seats and skin-to-skin touching. Many doctors refused to treat or even see patients suspected of having HIV. In the wake of this, many LGBTQ people came to distrust the media and public health measures associated with it. At the same time, the Reagan government sat idly by while hundreds of thousands of people contracted HIV, with more than one-third dying by 1990.

It would take several years before any kind of treatment was available for HIV, and when it was, it was prohibitively expensive. The first anti-retroviral medication, called AZT, cost $10,000 for a one-year supply! It was the most expensive drug in history when it was first released in 1987. While Haring was able to afford it thanks to his art, his friends and many others could never afford this treatment. AIDS became the crisis that it did because of the inaction of capitalist governments. It is simply not profitable to solve public health emergencies. There is a reason the famous book on the subject is called, And the Band Played On!

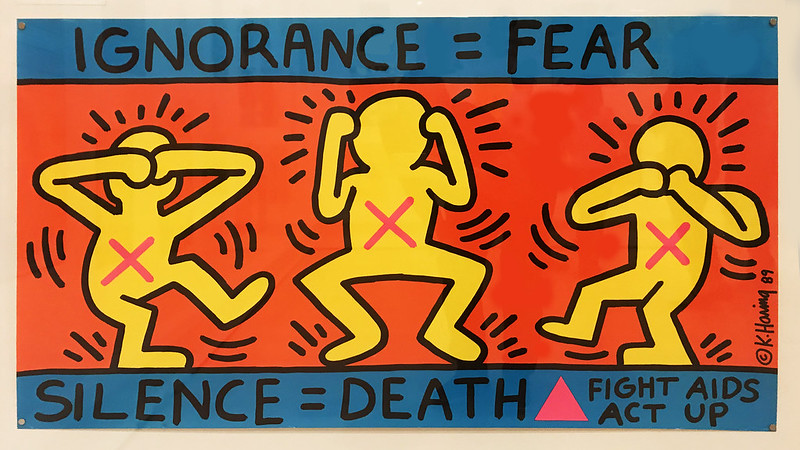

From 1988 onward, Haring created hundreds of drawings, posters, and murals to promote safe sex, educate about AIDS, and promote AIDS-related causes. It was during this period that Haring created his most famous art piece, known as Ignorance = Fear. The piece recreates the Japanese pictorial maxim of the three wise monkeys, which represent the saying: “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Haring’s piece promoted public awareness and health education about AIDS in partnership with ACT UP, an activist group fighting AIDS. This piece, as well as Haring’s other works on AIDS and safe sex, were brave attempts to counter this climate of fear and ignorance. Haring eventually passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1990, just two years after his diagnosis.

Haring took the styles of the mainstream art world and used it to challenge the status quo by turning it on its head. His art was ultimately a push back against the gimmicky and greedy commercial art that sought to conquer the psyche of the masses. His response was to fight back by using his art to address the problems burdening everyday people. His art still lives on in the collective memory of the masses today for very good reason. He attempted to step up when it seemed like no one else would. Unfortunately, Haring’s artwork — like any art – can only go so far in fighting against capitalist barbarism.

The legacy of the Pop Shop and the failure of ‘fast art’

After Haring’s death, the Pop Shop continued on under the control of the Keith Haring Foundation. Unfortunately, in 2005, the Pop Shop would suffer the same fate most small businesses do under capitalism: shop closure. Rent in the New York neighborhood where the shop was located skyrocketed, while the shop’s sales could not support itself anymore.

Despite this, the Pop Shop helped to set a new precedent for artists in the 21st century—though not exactly the kind that Haring intended. The idea that artists could make their work “accessible” while collaborating with enormous corporations has gained rapid traction since Haring and the Pop Shop. The Keith Haring Foundation has partnered with such corporations as H&M, Uniqlo, Adidas, and Abercrombie & Fitch. In 2020, the foundation made $10 million in revenue from collaborations.

Haring explicitly disagreed with putting his art on anything and everything just to sell it. In the same biography, he states: “I mean, we could have put my designs on anything.” The point was not to sell as much of his art as possible, but to create as much art as possible for people to enjoy.

Haring’s motivations for the Pop Shop were of an entirely different character than those behind the foundation’s collaborations today. The foundation argues that this commercialization is in keeping with Haring’s spirit of “accessibility”. It is hard to stomach such a disingenuous statement from a foundation claiming to represent the artist who wrote, “Money doesn’t mean anything. Money breeds guilt (if you have any conscience at all). And if you don’t have any conscience, then money breeds evil.” Haring was uncomfortably conscious of the fact that the Pop Shop was a contradictory initiative. For him, combining the idea of “art for everyone” with the profit motive was his only choice to create widely accessible art.

The actions of the Foundation today go directly against Haring’s wishes of “maintaining and protecting his artistic legacy after his death.” The previously mentioned collaborations resulted in simple prints of his most digestible, apolitical work on regular clothing. They have been torn from their origins as “art statements”, and turned into little more than graphic design on expensive clothes. They lack the expression of ideas and emotions that were effervescent in Haring’s work. Haring’s foundation has completely abandoned his philosophy in pursuit of the almighty dollar.

Is ‘art for everybody’ possible?

In the past ten years, the art market surrounding Haring’s work has exploded. Several of his pieces have sold at prices in the millions at auction. It is estimated that his entire art catalogue is now worth $100 million US! For example, a small painting on his bedroom wall was considered so valuable that the wall was removed from the house, and auctioned for $140,000! In another despicable display of the commodification of art under capitalism, previously unseen works of Haring’s are now being released as NFTs.

Haring’s entire collection of work, famously dedicated to “everybody,” is now mostly stuck inside private collections, hidden away from the very public he hoped to create it for. Where his work does reach the public, it is reduced to big-brand graphic design collaborations devoid of meaningful artistic intention.

Haring nobly and boldly fought to find a “third way” between commercial art and exclusive high art. At certain moments, particularly when connecting to social movements, he was able to reach the masses while retaining his artistic independence. But overwhelmingly, Haring’s aspirations were blocked by the forces of capitalism. Capitalism offers essentially two ways for artists to make a living and circulate their work: either make art for the ultra-wealthy, or adhere to the dictates of the market and abandon your artistic integrity. There are certainly many artists with a truthful artistic vision who may attain certain opportunities: small gallery shows, local museum displays, and the like. But at a certain point, they will be faced with the choice of either selling out or remaining stuck in relative obscurity.

This contradiction brings to mind a question asked by Trotsky long ago: “How many Aristoteles are herding swine? How many swineherds are sitting on thrones?” Today, there are no doubt countless Mozarts making McNuggets, and artists like Keith Haring dying of preventable disease, while a handful of talentless art collectors hoard human culture.

Haring was fortunate and principled enough to rise to acclaim without forfeiting his political messages or artistic integrity, but he found no sustainable way to consistently connect his art to the public without succumbing to the profit motive. This is because the distribution and promotion of art is an economic question. The Pop Shop could not compete on the market, and only the art dealers remained as a means for Haring to make his work consistently visible.

Haring’s goal of freely and independently connecting his art with everyday people could never have been fulfilled by himself alone, because no individual can overcome the laws of the capitalist system.

In reality, the realization of Haring’s goals will take a revolution, and that task is up to the masses of the workers and oppressed to whom Haring’s art was dedicated. By uniting to overthrow capitalism, the working class can liberate art from the stranglehold of the capitalists and make “art for everybody” a reality, in both production and distribution. Not only would this transform the relationship between artists and the public, it would transform art itself.

Fight for the right to art

The Russian Revolution of 1917 proves this in practice. With the institution of a planned economy by and for the workers, art really was for everybody. The result was nothing short of a revolution in culture. All of Russia’s artistic legacy, previously held under lock and key by the tsarist aristocracy, was put into public museums. The heights of artistic culture were made accessible to everyone. Not only was art now available en masse, it was created en masse. Spontaneously, the energy and emotions of the revolution were expressed in massive public street performances, parades and dances. But the role of the workers’ state was just as important to artistic creation. It oversaw the formation of “creative unions”, organizations for creative occupations akin to the trade unions. The creative unions provided programs for their artists to receive extensive education and instruction in their craft. Importantly, the artists were paid by the unions so that they could devote themselves wholly to their craft without the burden of wage labour. Further, admission to the unions was based on merit alone—an amazing far cry from the prohibitive financial barriers posed by art schools under capitalism. It is no wonder that art and culture flourished in the newborn Soviet Union, giving rise to artistic movements which still influence culture today. Once art was opened up to the masses of Russia, the energy of an entire people was poured into it.

While these achievements would eventually be crushed by the Stalinist bureaucracy’s paranoid and restrictive policy toward art, they give us a precious glimpse at the possibilities of art under communism. For a brief but incredible time, art truly was the province of every human being in the young Soviet Union. As a result of being in the hands of the public, art itself was transformed. It was neither a rarefied sphere for the wealthy, nor just another avenue of commodity production. It was the collective possession of the masses, and a living reflection of their wills, aspirations, and creativity.

Therefore it is in the ongoing tradition of revolutionary struggle, led by the masses for whom Haring’s art was made, that his goals are truly represented—not the lucrative brand deals of the Haring Foundation. To truly make art for everyone, we have to fight to take it from the capitalist class which has withheld it from us in the first place. Not only does the commodification of art make it inaccessible to the majority of people, it betrays the very function of art.

Haring believed that art “brings together man and the world,” providing touchstones that connect the human experience across incredible time and distance, even to our prehistoric ancestors. But when art is commodified, it is ripped from its very function. What would today’s commercial art teach of our experience to the humans of the future? Only that we were dominated by the inhuman logic of the profit motive. Haring is right that art brings together humanity and the world, but we would add that capitalism rips them apart, and it will take a revolution to bring them back together.