No aspect of daily life is out of bounds for communists, including art and culture. But we don’t approach art as bourgeois critics do. Nor as Marxist school teachers, grading works of art according to how well they expound a revolutionary line. Art does not need to politically justify its existence—but when we do look at it politically, what’s really interesting about art is that successful works reflect something about the society they were created in. After all, to gain popularity art has to speak to the masses.

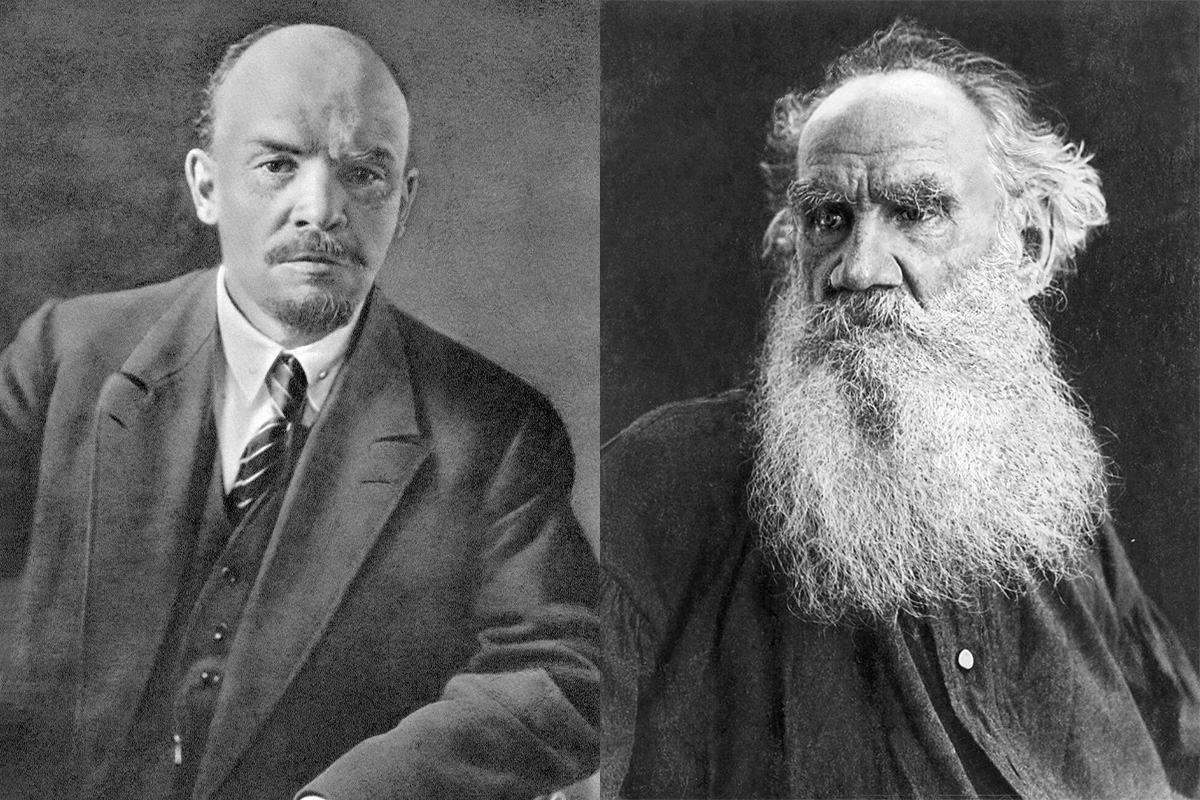

This is the way that Lenin approached one of the greats of Russian literature, Leo Tolstoy, in a number of short articles written between 1908 and 1911.

Best known for sweeping novels like War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Tolstoy’s work presents broad casts of complexly layered characters, grappling with historic events and social pressures. Tolstoy himself had eclectic beliefs, blending Christianity, anarchism, and pacifism. Such was Tolstoy’s influence that, despite his discouragement, a Tolstoyan social movement sprung up in the 1890s. As the consciousness of the Russian masses developed, however, Tolstoy fell out of step—particularly after the 1905 revolution, which he rejected. As Lenin wrote,

“Tolstoy reflected the pent-up hatred, the ripened striving for a better lot, the desire to get rid of the past—and also the immature dreaming, the political inexperience, the revolutionary flabbiness.”

“Leo Tolstoy as the Mirror of the Russian Revolution”, 1908

When a beloved artist has bad politics, the temptation is to separate the art from the artist. Lenin doesn’t do that. Instead, he discusses how the very thing that makes Tolstoy a great writer is also the source of his weakness: that he so fully represents the Russia of the past century, with all its contradictions.

“Tolstoy’s works express both the strength and the weakness, the might and the limitations, precisely of the peasant mass movement. His heated, passionate, and often ruthlessly sharp protest against the state and the official church that was in alliance with the police conveys the sentiments of the primitive peasant democratic masses, among whom centuries of serfdom, of official tyranny and robbery, and of church Jesuitism, deception and chicanery had piled up mountains of anger and hatred.

…

“The contradictions in Tolstoy’s views are not contradictions inherent in his personal views alone, but are a reflection of the extremely complex, contradictory conditions, social influences and historical traditions which determined the psychology of various classes and various sections of Russian society in the post-Reform, but pre-revolutionary era.”

“L.N. Tolstoy”, 1910

To find an audience, artists have to be attuned to their moods, their experiences and mentality. The most pretentious artists speak to a narrow audience, the best can connect with the widest layers. This connection is what allows them to act as a mirror for society. And this sense of connection runs through all of Tolstoy’s work, in the richness of his characters and stories. It’s what made Tolstoy a great writer, and what shaped his politics, for better and for worse.

“But the uniqueness of Tolstoy’s criticism and its historical significance lie in the fact that it expressed, with a power such as is possessed only by artists of genius, the radical change in the views of the broadest masses of the people in the Russia of this period, namely, rural, peasant Russia. … Tolstoy mirrored their sentiments so faithfully that he imported their naïveté into his own doctrine, their alienation from political life, their mysticism, their desire to keep aloof from the world, ‘non-resistance to evil’, their impotent imprecations against capitalism and the ‘power of money’.”

“L.N. Tolstoy and the Modern Labour Movement”, 1910

Lenin recognized the worth of studying Tolstoy for both his strengths and weaknesses, and the insights they provided. He also saw for himself that if communists don’t highlight what the working class can learn from art, then the bourgeoisie will obscure those lessons. After Tolstoy’s death in 1910, liberals jumped to deify him as the “universal conscience” of Russia, focusing on his pacifism while ignoring his criticism of the church and the state. In his response, Lenin used his understanding of Tolstoy as another means to fight against bourgeois liberalism.

“Tolstoy’s indictment of the ruling classes was made with tremendous power and sincerity; with absolute clearness he laid bare the inner falsity of all those institutions by which modern society is maintained: the church, the law courts, militarism, ‘lawful’ wedlock, bourgeois science. But his doctrine proved to be in complete contradiction to the life, work and struggle of the grave-digger of the modern social system, the proletariat. Whose then was the point of view reflected in the teachings of Leo Tolstoy? Through his lips there spoke that multitudinous mass of the Russian people who already detest the masters of modern life but have not yet advanced to the point of intelligent, consistent, thoroughgoing, implacable struggle against them.

…

“By studying the literary works of Leo Tolstoy the Russian working class will learn to know its enemies better, but in examining the doctrine of Tolstoy, the whole Russian people will have to understand where their own weakness lies, the weakness which did not allow them to carry the cause of their emancipation to its conclusion. This must be understood in order to go forward.

“This advance is impeded by all those who declare Tolstoy a “universal conscience”, a “teacher of life”. This is a lie that the liberals are deliberately spreading in their desire to utilise the anti-revolutionary aspect of Tolstoy’s doctrine.”

“Tolstoy and the Proletarian Struggle”, 1910

Great art is more than just great art. It’s a way to gain insight into the society that it sprang from, a way for the working class to gain that insight. It has political significance beyond the intentions of the artist. For communists, it’s not just worthwhile to enjoy art, but to study it.