This is the second of a two-part article. Read part one here.

The occupation and the riot

The computer centre was a well-chosen target. The computers themselves were bulky, and could only be operated with stacks of punch cards and reels of tape, meaning that the computer centre, having centralized all these elements into one place, was the heart of all of the university’s computational work. Taken together, it was Sir George Williams’ most valuable asset. The occupation brought a central part of the university’s functions to a standstill.

At first, there was a carnival atmosphere in the occupiers’ camp. The students passed the time listening to calypso music, dancing, and above all discussing politics—in particular the struggle for Black liberation. They even organized themselves into committees to clean the occupied floor, and to look after the University’s computers. In this way the occupation went on peacefully for two weeks.

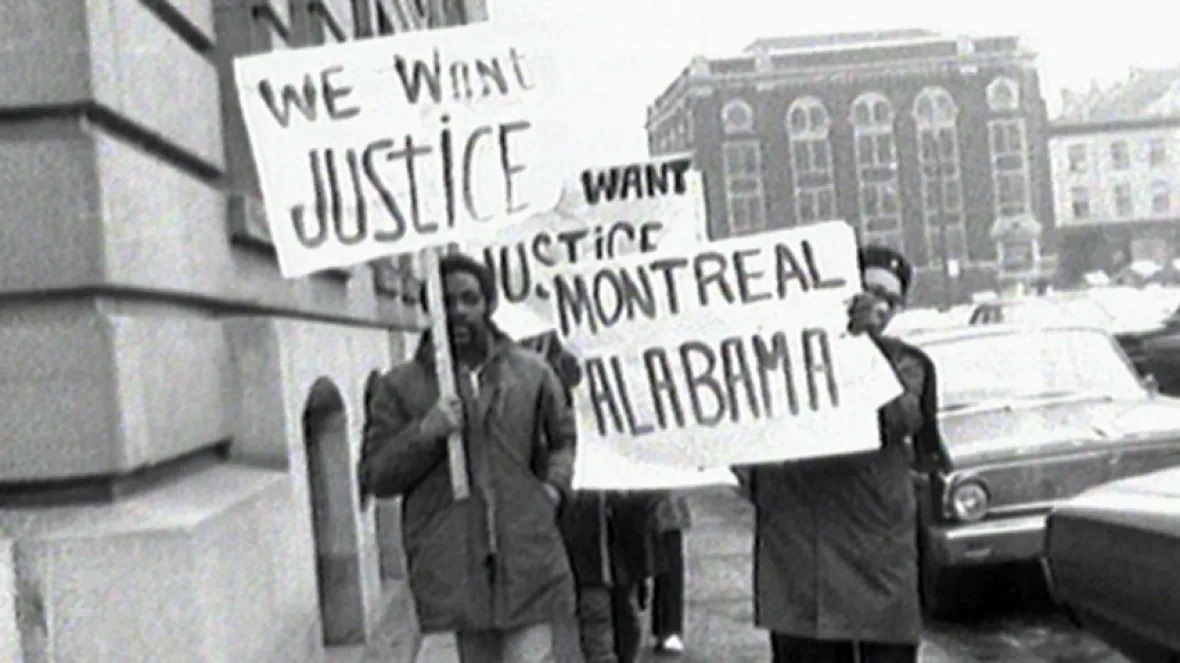

Of the 200 students who began the occupation, some left to go to work or so see their families, and they were replaced by other workers and students from Sir George Williams, McGill and from the broader community. The computer centre occupation even had its imitators—another group of sympathetic students organized a solidarity rally on the university mezzanine and led more supporters to occupy the faculty lounge. A network of workers and students from across Montreal came together to keep the occupation supplied, providing food and other necessities. Protestors also began to gather on the streets outside of Sir George Williams University to march in solidarity with placards.

With the wide support of the occupation, the only thing the administration could do is let the occupation continue, and to wait for their opportunity to clear it out. As important as the computer centre was, it was only one branch of the university’s operations. The rest of the university could still operate much as it always had, apart from the uncomfortable situation on the ninth floor and the protesters marching outside. Playing for time, they finally agreed to renegotiate with the six original complainants on a new hearing committee.

The students accepted the administration’s offer as an olive branch and agreed to negotiate. Within the ranks of the occupiers there was a sincere belief that they would win their demands quickly and go home victorious. Among the administration, however, this was their means of drawing the occupation out, allowing fatigue and demoralization to set in inside the confines of the computer centre.

Across Montreal, particularly among francophone workers and youth among whom the national liberation struggle was increasingly taking the form of a class struggle against the bosses, the struggle of the Sir George Williams students struck a chord. The Union of Quebec Students (UGEQ) at the time wrote a statement in support of the occupiers, and the Montreal Central Council of the Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN), the most radical Quebec trade union federation at the time, issued a similar statement. There was a large reserve of support from wide layers of workers and youth.

Statements of support such as these serve an important role in cutting across the slander of the bosses and the media. They help to demonstrate that the struggles of workers and youth from all backgrounds are intrinsically linked and directed against one common class enemy. For the movement to grow, however, and to overwhelm the forces attempting to suppress it, it is necessary to link these various struggles against racism, national oppression, and exploitation under a set of common class demands. Unfortunately, in the Sir George Williams Affair this broader support remained largely passive. The various struggles taking place in Quebec were never concretely linked. The labour movement remained aloof from the students’ protest, and the students themselves placed all their hope in the occupation. The only course of action to achieve victory would have been to spread the movement beyond the four walls of the computer centre by appealing to other groups to join them in protest. This never happened; instead, the students waited and the labour movement watched.

The negotiations stretched on with little progress and fatigue began to set in. Of the 200 who started the occupation, their numbers dwindled to 100. A protest cannot go on forever, and once the occupation began to stagnate it also began wearing away at the occupiers’ endurance. The carnival atmosphere, which had filled the early days, made way for the desperate desire for a quick resolution. Then, quite suddenly on February 10th, after two weeks of waiting, the students were told that an agreement had been reached between the original complainants and the administration. The administration had given up, and they had won. There was an outpouring of relief, and the students celebrated.

But the next day they discovered the supposed “agreement” had been a lie—the administration had reneged at the last minute, and demanded a return to negotiations. Everything would have to start again from the very beginning. After two full weeks, there was still no end in sight.

Whatever relief the occupiers had felt the night before quickly turned into despair. They felt, and rightly so, that they had been manipulated. After 14 days of peaceful occupation, they began to retaliate. The students threw a mass of furniture—tables, desks, chairs, anything they could find—into the stairwells. They shut down the elevator, cutting off access to the upper floors of the university. At long last, the administration had its moment. They called on the Montreal police to put down the occupation. More than a hundred riot police arrived to dismantle the barricades and arrest the occupiers.

Realizing that they were surrounded, that the police were storming the building, the occupiers broke windows and threw computer punch cards into the streets below by the thousands. Some smashed the university’s expensive computers with fire axes. When the riot police tried to climb over the makeshift barricade the students sprayed them with a firehose. Somewhere in all the commotion, some unknown person started a fire. Smoke filled the ninth floor and poured from the broken windows. Exactly who set the fire remains a mystery—the administration and the police blamed the students, meanwhile the students said that the fire had been started as a pretext to beat and arrest them en masse.

The riot police attacked the protestors with clubs, boots, and their fists—directing the worst of their violence against the Black students. According to one of the student protestors: “Many students including myself were beaten and tortured by the Montreal Police. Students were forced to lay down on broken glass on the floor and were beaten with clubs… One of the students from the Bahamas suffered a brain aneurysm, and she died shortly after. Her parents believe she died because of the beatings she received that day.”

In all, 97 students were arrested. The media reported in the following days that the cost of damages caused by the riot and the fire were upwards of $2 million, making the Sir George Williams Affair the most costly student protest in Canadian history at that time, and it would remain so for nearly half a century.

National and international impact

Where the administration had left off in channelling prejudice and bigotry, the bourgeois media picked up. Over the following week the Montreal Star, for example, ran the headline: “Maoists Caused Violence” alongside others like “Police Stayed Cool Under Pressure” and “Riot Squad Impressive”. There was an attempt by several politicians and pundits to blame the Affair on a small cell of radical conspirators. Others claimed it was senseless (one academic went so far as to call it Freudian) outpouring of violence. The Sir George Williams Affair had by this time become a national event—and so the campaign to defame the students in the eyes of the working class became a national project.

In the aftermath of the Sir George Williams Affair, student leaders like Kennedy Frederick were forced to flee the country while others like Rosie Douglas faced harsh prison sentences. After being released from prison Douglas would remain under constant RCMP surveillance until he was eventually deported in 1976. Those who remained in Canada found their lives profoundly marked by the legacy of the Sir George Williams Affair.

The brutal repression by the Canadian state sparked outrage both in the Black community in Canada and abroad. In the following years, Montreal experienced a proliferation of Black liberation newspapers and journals, published by activists and revolutionaries of various political currents.

The violent treatment of the Sir George Williams students also kickstarted a radical student movement at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad, which later converged with the seething unrest of the Trinidadian working class. The Governor General of Canada was stopped on his way to speak at the University of the West Indies by blockades organized by outraged students. These student protests would eventually spill over into generalized protests and strikes by the workers and youth against the Trinidadian government and the foreign domination of the country by British and Canadian imperialism. In February 1970 a march was held outside the Canadian High Commission in Port-of-Spain in which one demonstrator told the media: “We are aware of what is being done to our brothers in Canada and we intend to take serious positive action if those boys do not get justice.”

Inspired by the international struggle for Black liberation, the Sir George Williams students themselves helped to inspire a revolutionary movement in the Caribbean. While the Sir George Williams Affair was quickly buried here, it took on an international significance. It became living proof of the fact that the struggle against oppression and exploitation does not adhere to national boundaries.

Lessons for the movement

Lessons in militant struggle are quite often learned painfully. How was it that a formal complaint against a racist professor managed to escalate into one of the largest student riots in Canadian history?

Quite often in social movements a more-or-less accidental event expresses an underlying necessity. In the full historical picture of the Sir George Williams Affair, Perry Anderson plays such an accidental role. Were it not for his individual racism it is inevitable that the anger which had been building amongst the Caribbean students at Sir George Williams would have found another point of expression—possibly in another professor, or more likely, in another aspect of their daily oppression entirely. After this initial accident, however, like the first spark which ignites a mountain of combustible material, the contradictions inherent in the situation prepared the way for the eventual explosion.

Once the students realized that they could not depend on the administration to address the issue, they turned to their own means. They began mobilizing their classmates, held teach-ins and rallies, and in the process applied massive pressure on the administrators from below. This, and not “the Anderson Affair” itself, was the underlying cause of the Sir George Williams Affair. The administration was forced to take actions which were against its own interests under the pressure of the protesting students and their supporters. This continued to the point that the right of the administration to govern the campus was brought directly into question.

Universities adopt many of the structures which pervade capitalist society at large. Unelected Boards of Governors are filled with appointees from outside the university—often from government departments, major businesses, and banks—to head the administration and ensure that the university runs efficiently and for the benefit of the capitalist system. Whatever representation workers and students are granted in these bodies is most often symbolic and negligible. They are not run for the benefit of either the students, who pay inordinate tuition fees to attend the universities, or for the benefit of the staff, without whom they would not function. Rather, universities under capitalism are operated for the benefit of the capitalist class.

It is in this way our universities, our so-called “temples of learning”, are turned into conveyor belts for ideas and prejudices which are of benefit to the ruling class. This is still the case today. While Concordia University’s administration today prostrates itself before a plaque commemorating its past sins during the Sir George Williams Affair, it still refuses to address the recurring issue of the sexual harassment of their teaching assistants and students. Under capitalism, in all spheres of life, the fight against oppression is an uphill battle which the ruling class never takes seriously until it is forced to by militant action.

Once the authority of the administration was undermined, there was an ever-present danger that this struggle, which began simply as a protest against one racist professor, could boil over into an open struggle over the question of who should control the university. In fact, the consciousness of a layer of the protestors was moving organically in this direction! During the battle over the hearing committee the students had begun to demand that students themselves should be appointed. Later, certain layers of the occupiers’ camp even used the affair to discuss the question of the democratic control by students and staff over the university. If these two groups were to unite against the administration the demand could easily be raised that it should be the students and the staff themselves who democratically decide how the university should operate. Sadly, this didn’t happen.

Similarly, if the Black students at Sir George Williams University were allowed to militantly protest their oppression by occupation and win, this would set a dangerous precedent. In the context of the late 1960s in Quebec, with growing numbers of workers and students taking to the streets in strikes and protests against the imperialist domination of Quebec and their exploitation as workers, other groups could have been inspired to also fight against their oppression and exploitation. To prevent the protest from igniting a wider social movement across the rest of the province, the ruling class had to make an example of the students.

It was for this reason that the student protestors came into direct confrontation with capitalist institutions like the state and the media. While these institutions, much like the universities, portray themselves as impartial arbiters of justice and truth they are in reality the instruments the ruling class use to protect their rule. They too reflect the ideas and the interests of the capitalist class, and at the same time reflect its prejudices.

It is common for both representatives of the state and the media to divide working people along racial, religious, or other lines and to portray their interests as diametrically opposed to one another. In this way, whether consciously or not, they defend against the possibility that these groups could unite in order to struggle for their common interests as oppressed workers and youth. The Sir George Williams Affair provides a key demonstration of this fact. The united strength of the students forced the administration out of their own campus. It was therefore necessary to bury the Affair and the students under a mountain of slander and lies.

Similarly, the police as an institution of the state does not exist to uphold “blind justice“. It is the special body of armed men in defence of private property and the ruling class, organized and trained to put down any movement of the workers and youth which threaten the status quo. Even before the student occupation began, the administration at Sir George Williams University had gone to the police for security counsel on how to manage the rallies being organized by the students. In return for their advice, and for their help in brutalizing the protestors, the administration did them the service of not noticing their brutality. Principal O’Brien publicly praised the Montreal police for their “peaceful” handling of the Sir George Williams Affair, and several Montreal newspapers parroted that lie.

The struggle against racism, when faced with these massive instruments of division and repression, requires a truly mass struggle. Much in the way that the divide and conquer tactics of the administration were swept aside by the rallies and teach-ins organized on the campus, and by their special issue in the student newspaper, a militant struggle against racism on the scale of Quebec or of Canada must be able to cut across the reactionary manoeuvres of the state and bourgeois media. People who suffer directly from a given form of discrimination cannot be left alone to combat the brutality of the state and to answer the slander of the media by themselves.

This was the key limitation of the Sir George Williams Affair. While support poured in from francophone student groups and even from the CSN’s Montreal Central Council, this support never crystallized into mass solidarity demonstrations or campaigns. The students protestors never made the call for such demonstrations and the labour and student leaders across Quebec never thought to organize them. Had the connection been made between the national oppression of the workers and youth of Quebec and the racism faced by Black people in Canada, had an organization capable of demonstrating that these forms of oppression stem from the same root cause, the pressure would have mounted and the students could have won significant concessions on the fight against racist abuse on campus All history shows that it is through mobilizing on class lines that we can better fight racism and other forms of oppression.

As the present crisis of capitalism deepens, those who are most deeply affected are the most exploited and oppressed layers of the working class. Despite the inspiring mass struggles against racism in the 50s and 60s in America and the formal rights that have ultimately been won, Black oppression is alive and well.

Capitalism depends upon the exploitation of the overwhelming majority of society, the working class. In order to maintain the subjugation of such an immense layer of society it is necessary to divide it against itself. If certain groups of workers can be made to oppress and discriminate against others then the ruling class, the capitalist class, can maintain its privileged position as the owners of society without the fear that the workers will unite and begin to organize society democratically amongst themselves. Racism, as one of capitalism’s most crucial tools for dividing the working class against itself, is a necessary component of the capitalist system. As Malcolm X once said, “You can’t have capitalism without racism.” To this we can only agree, and add: you can’t end racism without ending capitalism.

The struggle for genuine Black liberation is at its core a struggle against the capitalist system. But as the ruling class today feels the earth moving beneath its feet, it will attempt to use all means at its disposal to unload vitriolic hatred onto the working class, stirring up racism, xenophobia, and all other means of division that it can find. As revolutionary Marxists, we must be prepared to counter such bigotry and to underline the systemic roots that racism stems from. If we want to see a genuine end to racism, we must be prepared to fight for the total unity of the working class and youth under the banner of the socialist revolution.