Part Three: Why the Red River revolution was defeated

But how did this inspiring mass movement, which ejected the governor, stopped the transfer of land, defeated the attempts of the counter revolution and united the Métis, go down in defeat with Riel fleeing to the United States?

The question of class divisions in the Métis movement has largely gone undocumented in much of the history written about this struggle. This is why the explanations as to why the struggle went down in defeat are also lacking. The class differentiation among the Métis is an essential fact, which helps us to ultimately understand why the resistance in 1869-70 and 1885 were not successful.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four

Previously, these sorts of class divisions and contradictory interests were unheard of in the Métis community. However, with the victory in the fight for free trade, a whole layer of Métis traders came into their own, began accumulating capital and developed narrow class interests all to their own. Rich traders like James Mackay, William Dease, Pascal Bréland, Charles Nolin, and Xavier Letendre all came to oppose the movement led by Riel. This made complete sense as the new layer of rich Métis fur traders yearned for access to new markets and hoped that Confederation would grant them this.

In Red River, while Riel was leading the resistance, the Council of Assiniboia, with rich Métis trader William Dease as a member, drew up a welcome address to MacDougall. Dease and another rich fur trader, Georges Racette, went to La Barrière with 80 men and tried to convince the Métis activists to dismantle the barrier and let MacDougall enter. At a mass meeting, in the course of the debate, the persuasive Riel had swung enough of Dease’s supporters to his side that even Dease bent under the pressure and voted for the resistance. While Dease showed up with 80 men, he left with only 60, 20 having defected to the side of the revolutionaries. All of the attempts of Dease and the Council of Assiniboia to stop the revolution ended up having the opposite effect as the ranks of the resistance swelled. Riel tried to have Dease arrested in February 1870 for conspiring with the Canadian Party but Dease managed to get away.

The clearest example of the Métis bourgeoisie was probably Pascal Bréland. Bréland rose to prominence as a fur trader in the 1840s and supported the free trade movement against the HBC. Bréland had married Marie Grant, Cuthbert Grant’s daughter and had used these connections to advance his fur trading empire to such a point that he became known as roi de traiteurs (king of the traders). When Cuthbert Grant died in 1854, Bréland bought almost all of Grant’s land and became the largest landowner in the St. François Xavier area of Red River. By the 1860s, he had become very wealthy and was appointed to the Council of Assiniboia. In fact, a series of rich Métis traders related to Breland were co-opted onto the Council as a way of placating the Métis.

In response to the developing revolutionary movement, Pascal Bréland and Soloman Hamelin fled Red River in the fall of 1869, bringing with them their families, servants and a throng of followers. During the winter Buffalo hunt, the largest Métis wintering camp at Qu’appelle, with over 1,000 Métis hunters, met in April 1870 to discuss the situation. At this huge assembly, there was general enthusiasm for the movement and most wanted to join Riel. However, Bréland and Hamelin, convinced them to remain neutral and to not support Riel. This was the equivalent of stabbing Riel in the back which significantly weakened and isolated the revolutionaries in Red River.

Contrary to the heroic struggles of the rising bourgeoisie against feudalism during the enlightenment era—most clearly exemplified in great events like the English, French and American revolutions—the bourgeoisie in Canada was cowardly and recoiled from revolution. This was the case during the rebellions of 1837-38 as well as during the Métis uprisings of 1869-70 and 1885.

The new bourgeois layer of the Métis population was not eager to revive the revolutionary movement and take up arms to defend the land. By this time, a significant section of the Métis population either worked for them or worked for the HBC shipping their furs and other cargo. This layer of nouveau riche was therefore in no hurry to rile up the population to defeat the Canadian Party threat. These people were essentially the fifth column within the movement who would ultimately undermine the struggle and contribute to its defeat.

As the movement was forced to take more and more radical measures (such as seizing the HBC headquarters at Fort Garry), many of these Métis bourgeois moved into open opposition to the movement and started to directly undermine it. But the seizure of HBC property was absolutely essential to feed the troops and fund the revolution. Here we see how the Métis bourgeoisie recoiled with horror from taking decisive action to win.

The reality is that it was the class line that was the fundamental dividing line in the movement. Most of the opposition to Riel was on a class basis from rich Métis traders, the majority of which were in fact French Catholics. Most of Riel’s supporters were tripmen who worked on the HBC boats as seasonal wage labourers. It is not surprising the rebellion really got underway in October-November when most tripmen would have been back in Red River as the freighting season was over. They even created their own organization called the Captains of Boat Brigades. This fact only made the rich Métis traders recoil further.

There is a lesson here for the Indigenous movement for today. As is so often the case in national liberation struggles, the bourgeois elements of the oppressed nationality prove incapable of leading the movement and end up faltering and, ultimately, siding with the oppressor.

The crisis of revolutionary leadership

In addition to this, there was the question of the subjective factor: that of revolutionary leadership. Riel, in spite of all of his laudable characteristics, was quite naïve and contributed to the disarming of the movement in the face of the oncoming counter-revolutionary attacks of MacDonald.

The first case of naivety was in the negotiations with Canada. Riel and some of the other Métis leaders trusted that MacDonald and the Canadian government would negotiate in good faith. However, it was not difficult to see that while the Métis delegates were arguing for their Bill of Rights with the representatives of the Canadian government, an army was being prepared behind their backs.

Colonel Wolseley wrote privately that “the government is anxious that everything should be done quietly for as they expect some vagabond delegates from Mr. Riel’s government to go to Ottawa they do not wish it to appear that they are preparing for war whilst they are also professing to treat amicably.” This two-faced way of doing things seems to be ingrained into the Canadian state.

The result of the negotiations with the Canadian government, which was the Manitoba Act, contained a promise of 1.4 million acres of land for the Métis and their children. However, this promise was not worth the paper it was written on and they had absolutely no intention of honouring it. There was no way that the financial and industrial capitalists in the east would allow such a large quantity of land to be out of their reach and a potential barrier to the unification of the state. We see the same phenomenon over 150 years later with continual conflicts over Indigenous land claims. The provisional government voted to accept the draft bill which received Royal Assent and became law on May 12, 1870.

Riel thought that because they had an agreement, it would be honoured. This proved to be a fatal mistake and this is a key lesson for revolutionaries today. Real power exists in the real world, in the balance of forces, and when push comes to shove the law is worth nothing if force doesn’t exist behind it. Conversely, if there is a greater organized force which defies a law, that law cannot stand in the long run.

Even if the goal was to be admitted into the new Canadian state, the only thing that would possibly create the conditions for a more amicable entry would have been to back up the Bill of Rights with force of arms. As the old adage goes, weakness invites aggression and MacDonald must have been snickering to himself about the naivety of Riel as he prepared to unleash bloody reprisals against the Métis revolutionaries.

Macdonald prepares for war

While the negotiations were taking place, a force of over 1,000 men was being raised to put down the movement. The reactionaries held mass meetings in the Protestant community in Ontario to drum up support for crushing the Métis rebellion. For the execution of Scott, they demanded the lynching of Riel. Of the 1,051 people in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, over two-thirds were recruited from Orange Lodges.

However, the success of this force was not a foregone conclusion by any means. The Provisional Government led by Riel was the power in the region, and the Canadian government had little support west of Ontario. Of the 12,000 people in Red River, over 8,000 were Métis. There were thousands of young men, armed and highly skilled with a gun. They also had a long and proud tradition of resistance with many victories under their belt. As well, none of the First Nations were too excited about Confederation and the poor Irish and Scottish settlers also had legitimate concerns.

While the Canadian Expeditionary Force left for Red River on May 25, it was a treacherous journey along the rivers and they did not arrive till Aug. 25. From a pure military point of view, while the force sent by the Canadian government would have potentially had more troops, they were extremely vulnerable along the way and a small force could have caused them serious damage without suffering much hardship.

In a battle taking place in the wilderness of Ontario or Manitoba, tactics, strategy and a general knowledge of the lay of the land are infinitely more valuable than sheer numbers.

This was later admitted by one of the officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force who was quoted in the Montreal Gazette saying: “Almost every officer in the detachment agrees with me—a hundred determined men with a couple of guns, could not only have, over and over again, sent our boats to the bottom, but have kept the whole detachment at bay and in fact caused its return.”

Then he continues, explaining that the real reason for the success of the counter-revolutionary force was precisely the actions of the leadership of the movement they were sent to crush:

“But for Riel’s command of his men, but for his strong personal influence and predilection for Canada and her institutions… the Canadian expeditionary force would certainly have never reached Fort Garry this year.”

Gabriel Dumont, famed Métis leader of the hunt, pledged to raise an army of 500 warriors but Riel argued against attacking. In addition to this, the Ojibwa were not too pleased about a massive military presence passing through their land. However, they were persuaded not to attack them by an influential Métis trader, Nick Chatelain.

In the meantime, Riel traveled to the wintering camps at Winnipeg and White Horse plain where at mass meetings he read Wolseley’s declaration which was ironically named “we come in peace.” Riel had this declaration printed and distributed and even had a celebration planned for the new governor’s arrival. Riel thus sent the bulk of his men home, completely disarming the revolution in the face of the coming catastrophe.

When Riel and the other leaders realized that there was not a governor, but an army that was coming to arrest them and crush the resistance, they fled to the United States. Riel, Nault and Lépine all fled and the population was left to fend for itself.

This highlights the absolute disastrous role played by the leadership, which let a favourable situation slip due to naivety.

The reign of terror and the fallout

Following the events of 1869-70, the Canadian government unleashed a reign of terror against the population of Red River. The Canadian Expeditionary Force arrived in Red River in late August and proceeded to rape, pillage and plunder. This reign of terror lasted for the next two and a half years. The purpose was to drown the revolutionary democratic movement in blood.

Anyone who was suspected of having any ties to Riel or the Provisional Government were hunted down. The mass public meetings which had become a regular occurrence were now met with violence and dispersed. Elizear Goulet was murdered and Andre Nault was beaten half to death. Métis traders had their furs confiscated and their homes ransacked.

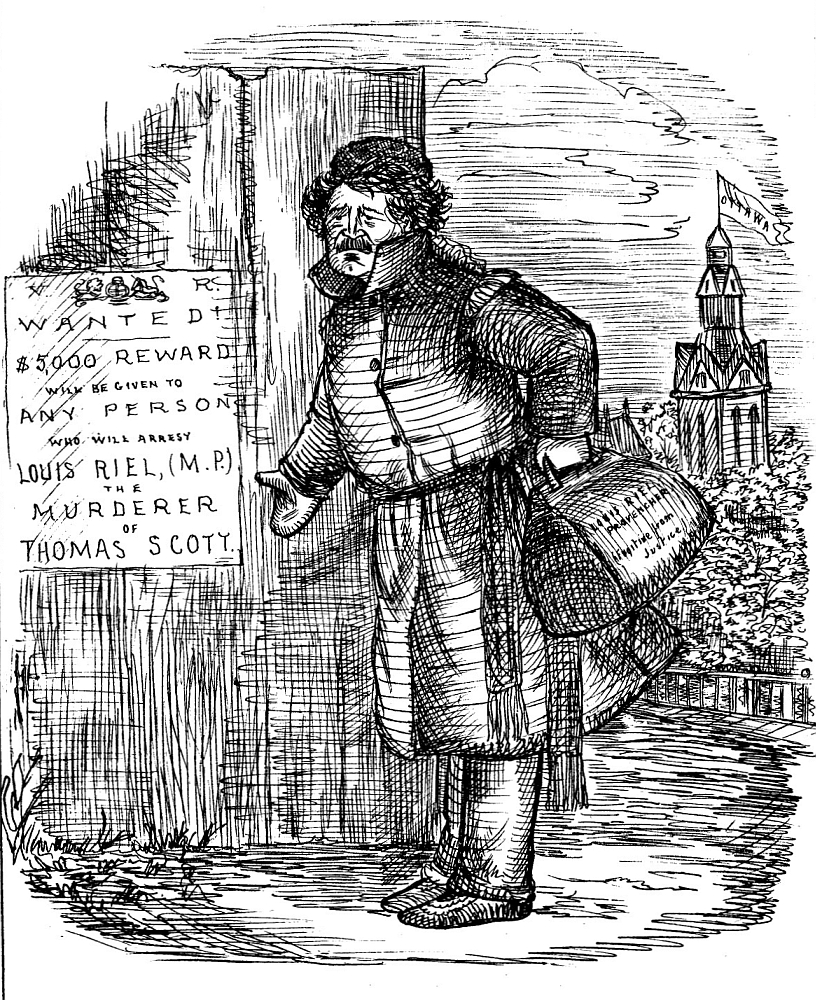

The Canadian government put a bounty of $1,000 on Riel’s head and Edward Blake, the premier of Ontario, upped that amount to $5,000. Eventually, amnesty was offered for Riel, but it never came as a new warrant was issued and Lépine was arrested. Finally, amnesty was offered but Riel had to accept five years in exile in the U.S.

As the Métis made up the majority of the population of Red River, they inevitably dominated the new Manitoba legislative assembly. However, voting was suppressed by limiting the franchise to male voters over 21 who legally owned a house in the district. As 62 per cent of Métis were under 21 and the majority of those left did not have legal claim under British law to the land or their residence, this drastically restricted the number of voters. This, in combination with brutal repression, led to an abysmally low turnout. These restrictions also meant that with just a small influx of settlers, Métis influence would be snuffed out within a few years.

In spite of this, Riel was elected to the Manitoba parliament on three separate occasions: once in 1873 and twice in 1874. He was, however, never allowed to sit which exposed the hypocrisy of this so-called democracy. The popularity of the 1869-70 revolution was shown when the legislative assembly tried to pass a motion calling for compensation for those who lost property during the revolution and punishment for the leaders of the resistance. Even though they watered down the motion, removing any persecution of Riel, only five people voted for this motion and it was defeated.

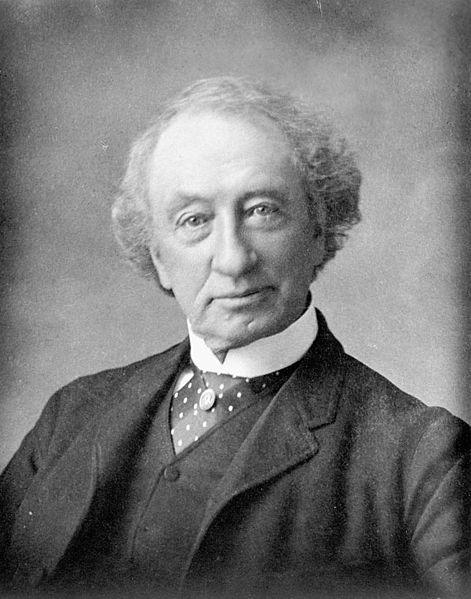

In less than ten years, this all changed. In 1870, 67 per cent of the members of the legislative assembly had resided in Manitoba before 1860 and 50 per cent were Métis. Only 8.3 per cent were English Canadian. By 1879 however, there was a complete shift with only 16.7 per cent of the legislative assembly being Métis while 54.2 per cent were English Canadians. John A. MacDonald’s plans had worked.

The result of this was that the Métis were completely disenfranchised. The government began a scrip system which was supposed to be a system in which the Métis could acquire formal title to their land. However, the promises of land were never kept. There was an immense bureaucracy which streamlined Anglo-Protestant land speculators in purchasing land but erected untold obstacles and used lies, fraud and forgery through the scrip system to steal the land from the Métis. For example, it took Riel’s mother 9 years to get her land recognized while his brother Joseph’s signature was forged on a document giving up his land.

Forced relocation

As Marx had underlined, one of the tasks necessary for the development of the bourgeoisie is the breaking down of local particularities and the founding of a nation state with a united national market. In France for example, the revolutionaries fought against the parochial interests of the Catholic Church and the feudal lords and proclaimed: “One France, indivisible.” Similarly, the United States of America was ushered in by a revolutionary movement of the masses which threw off the yoke of British colonialism and created the modern nation state of the U.S.A.

However, a lot had happened since these two great revolutions, and the situation in Canada was very different.The British, compelled by the revolutionary events of 1837-38, had decided it was better to reform from above than risk losing it all by provoking a revolution. This process allowed space for the rise of the nascent Canadian bourgeoisie, which developed its own interests separate from Great Britain. When confronted with revolution in 1837-38 and 1869-70, and later in 1885 (which we will deal with later) the Canadian capitalist class had ceased to be a progressive class and sided with the forces of counter-revolution, thus leaving the tasks of the bourgeois revolution up to the reactionary colonial regime.

The new Canadian bourgeoisie in the east desperately needed to establish control over the vast territory. In particular, concerns about annexation to the U.S. were very real and without easy access to the west coast, the development of the Canadian bourgeoisie would be hemmed in.

The aims of the Canadian capitalists can be summed up in the National Policy adopted by the John A. Macdonald government in 1879:

- Protection of domestic industries through a system of punitive tariffs on imported goods;

- The construction of a transnational railway infrastructure to connect the disparate parts of the new Dominion of Canada;

- An immigration policy to fill the Prairie West with agrarians.

In this endeavor, the young Canadian bourgeoisie had scored their first victory by crushing the Métis resistance in 1870. However, their historic mission was far from over. The North-West was still largely unpopulated—or to put it differently—it was not populated in any way that was particularly useful to capitalism. The Indigenous groups, including the Métis, who had played a vital role in the British colonial system during the fur trade era no longer played a productive role for capitalism.

They had in fact become more and more of a barrier to the interests of the Canadian capitalists who desired to build a railway across the country to tie the country together economically. What was needed was infrastructure to accommodate modern industrial capitalism. In order to do this, the Métis and First Nations peoples had to be crushed underfoot and swamped out with “peaceable and industrious settlers” in the words of John A. MacDonald.

While modern day conspiracy theories about “the great replacement” centre around alleged plans for governments to replace white people through mass immigration,one glance at history will show us that the exact opposite has been the case in Canada. The fate of the Métis after 1870 is a clear example of this.

In January 1872, 1,500 Anglo-Protestant settlers from Ontario arrived in Red River. They removed Métis stakes and took the land. Mass immigration from Ontario, combined with persecution against the Métis in newly formed Manitoba, led to mass emigration of the Métis population westward. In total, 4,000 Métis fled persecution, moving to the shores of the South Saskatchewan river. This forced relocation went on for over 15 years and by 1885 there were about 5,400 Métis in Saskatchewan.

In 1882, John A. Macdonald, who found himself back in power, was pushing an even more bold colonization plan through the Dominion Lands Act. This consisted in giving 10 million acres of land to colonization companies in order to quickly populate the western provinces. With the railway being built, this was a dream for speculators as the land would only increase in value once the last spike was laid and travel and transport was greatly facilitated. It should come as no surprise that two of the biggest land speculators were John Christian Schultz and Donald Smith. It was also not surprising that Schultz also got back into the media game, first with The Manitoba News-Letter and later with The Manitoba Liberal, which he used to shape public opinion to his liking. Here we see the roots of mass media in Canada, not as an impartial observer, but a mouthpiece for the Canadian ruling class. And this remains true to this day.