French President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to call snap legislative elections, with the final round this weekend, is proving a massive headache for the bourgeoisie. The prospect of Macron losing any semblance of a parliamentary majority is spooking the markets. At the same time, the rise of Marine Le Pen’s far-right Rassemblement National (RN) is provoking hundreds of thousands to take to the streets in protest.

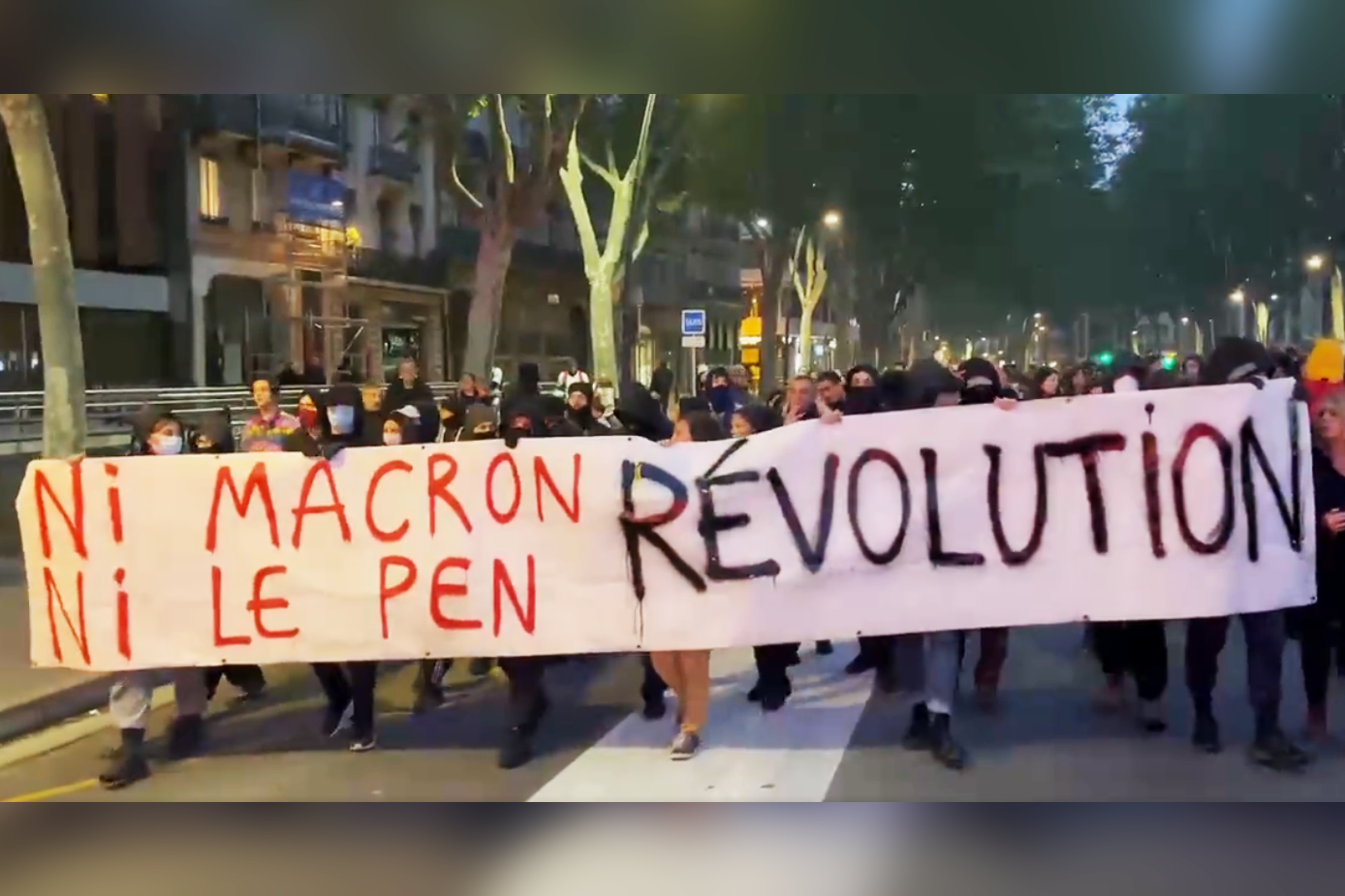

Since the success of RN (formerly National Front) in the European Parliament elections a month ago, hundreds of thousands have participated in protests against the party. The prospect of an RN government has roused the ire of young people and workers opposed to the party’s divisive politics.

On 15 June, over 600,000 people participated in 150 mobilisations against the RN across the country. This followed a number of smaller, militant demonstrations, in which participants shouted slogans against fascism, against Macron, and in solidarity with Palestine and migrants.

After the release of the election results on 30 June, anger against the softness of the leaders of the left was palpable. At an 8,000-strong protest in Paris, nominally for the left coalition ‘the New Popular Front’, the Socialist Party leader was booed by the crowd, with many present remembering the party’s last stint in power. La France Insoumise (LFI) leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon was also heckled for withdrawing candidates in favour of Macron’s party as part of a ‘Republican Front’ against RN.

Far from seeking compromises, the mood of the masses is for fighting back.

The ruling class in panic

The ruling class, on the contrary, are tearing their hair out. Whatever happens after the second round, there is no stable government to be found. What they need is a strong government to carry out attacks on the working class that the situation demands.

France is facing massive debts, and a large public deficit. Macron’s attacks on pensions went some way to reducing the latter, but it remains at 5.5 percent of GDP, meaning that for every €20 spent in France, €1 of additional debt is incurred by the government.

The overall government debt is 110 percent of GDP, one of the highest in Europe. And with the rising cost of government borrowing, this is pushing the cost of paying the interest ever higher. This year, this cost is estimated at around €55 billion, and it is increasing by €8 billion every year.

The situation has led to France being issued a warning by the EU that it has to reduce its deficit, or else. It is clear that, to balance the books, the bourgeoisie needs massive attacks on the working class, either by raising taxes (as we’ve seen in Kenya, with explosive results) or by further cuts and austerity measures. This was the programme of Macron, but he couldn’t muster sufficient support for it in the previous parliamentary configuration, and the new elections will make this problem worse rather than better.

Macron’s coalition, Ensemble (ENS) had 245 out of 577 seats in the National Assembly, but he is expected to lose more than half of those in this election. His occasional allies in the traditional right-wing Les Républicains (LR) party are set to lose more than 25 of their seats, compounding Macron’s difficulties. Most of those that will remain are looking towards Le Pen, hoping a pact with her will save them from oblivion.

Le Pen’s RN could take as many as 260 seats, up from 89 in the last National Assembly. The ‘New Popular Front’ (NFP) is likely to take around 180 seats, up from 131. Together with the rump of LR, RN could form a government, something that Le Pen has hinted at in the last few days.

This is a result of the collapse of the centre. In the first round, ENS got 21 percent, down from 26 percent in the last election. LR, the traditional right-wing party, got 6.5 percent, down from 13 percent. That leaves these two parties with 27 percent, down from 40 percent two years ago, and with half the support they had in 2017. It is abundantly clear that they can provide no stable base for the bourgeoisie to lean on.

By contrast, RN has almost doubled its support from 19 percent to around 33 percent. The support for the left has also increased somewhat. The NFP has around 28 percent support, up from the 26 percent vote share of NUPES (the previous left-wing coalition) in 2022.

Gideon Rachman from the Financial Times, in surveying the situation, gives a most glum perspective:

“At best, a parliament dominated by the political extremes would plunge France into a period of prolonged instability. At worst, it would lead to the adoption of spendthrift and nationalistic policies that would swiftly provoke an economic and social crisis in France.” (France could trigger the next euro crisis)

In essence, for Rachman, the best-case scenario is continued crisis and paralysis. The worst case scenario would be a government actually being formed, because such a government would create even more instability, both in the economic sphere and in the form of mass protests and resistance. In comparing the situation to the short-lived Truss government in Britain, his concern is that there wouldn’t exist the possibility of getting rid of such a government:

“In the UK, there was a mechanism to sack Truss quickly and to restore rational government. That task would be much more difficult in France.”

So, in Britain, the markets, the central bank as well as the MPs of the Tory Party itself managed to replace a Prime Minister that the ruling class didn’t want, restoring a ‘rational government’ (i.e. a government in the interest of big business), but Rachman doesn’t see the same thing playing out in France.

Crisis in Europe

Macron himself raised the prospect of ‘civil war’ should the left or the right gain power. This is clearly an exaggeration, typical of Macron. But there is a strong element of truth in what he is saying. The whole situation is pregnant with class struggle, and either a left or a right government would accelerate the process.

Furthermore, pro-EU bourgeois commentators like Rachman are concerned not just with France, but the impact this election will have on the EU as a whole.

The financial stability pact imposes strict conditions on the member states of the EU, and in particular on the members of the Eurozone. This is to ensure that some countries (read: Germany) don’t have to cover the debts of the other countries (read: France, Italy, Greece). Of course, very few countries are in compliance with the rules after 16 years of crisis, but France is one of the worst offenders.

In order to ensure continued stability, the EU will demand cuts and austerity from any French government. In order to get to the required target, the government needs to cut €70 billion in spending. It is unclear how the RN would deal with such demands. On the one hand, the person tipped to be a future RN finance minister, Jean-Philippe Tanguy, claims that the party will abide by the stability pact (“in the interest of French people”), and the party has publicly dropped its demand to leave the EU. On the other, they want to cut France’s EU contributions by €7 billion, which will not go down well in Brussels.

The bourgeoisie is divided on how to deal with the situation. One section is looking to bring RN into the fold, and try to make them ‘responsible’. In other words: to bring the party’s programme into alignment with that of the bourgeois, making it more amenable to the influence of the ruling class.

The FT reports on how big business is now looking at the RN as a potential partner:

“‘The RN’s economic policies are more of a blank slate that business thinks they can help push in the right direction,’ a Cac 40 [ie a top-40 company] corporate leader said of Le Pen’s party, which is ahead of other groupings in the run-up to the two-round vote on June 30 and July 7. ‘The left is not likely to water down its hardline anti-capitalist agenda.’” (French businesses court Marine Le Pen after taking fright at left’s policies)

This week, we find columnist Martin Sadnbu asking whether, in the case of RN the ‘cordon sanitaire’ should be dropped to reward the party for having moderated itself: “Le Pen’s attempted dédiabolisation and the party’s frantic rowing back on its promises suggest an interest in being successful within the system rather than in tearing it down.” (Europe’s cordon sanitaire against the far right may not work)

The example cited is Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who has graciously dropped her opposition to the EU, supported the war in Ukraine, and agreed to follow the EU’s fiscal rules. In other words, she has become a ‘responsible’ politician, one that aligns her interests with those of the ruling class and the ‘system’. They don’t mind her attacks on women’s rights, migrants, etc. The system can accommodate that, as long as she toes the line on the questions that matter to the banks and big business.

But the hope that Le Pen, or her Prime Ministerial candidate Bardella, will turn out to be another Meloni isn’t shared by everyone. Sunbau himself recognises that “elites” aren’t convinced by the RN.

The stakes are high. Already, the markets are running scared, worried about the potential for a clash with the EU, in particular. Given the belligerent nationalist statements that the party is known for, the question on the minds of the capitalists is: can they be trusted? They are also concerned that RN won’t continue France’s support for Ukraine, which the party has been a bit vague about.

Sandbu suggests that, maybe, they should put their faith in the “institutions”. In other words, the state, the press and other pillars of bourgeois society will moderate the RN and align it with the interests of the bourgeois and their system. In the end, they will probably not have much choice.

Collapse of the centre

Many of the bourgeois can see the writing on the wall. Macron’s ENS can not play the role of the main party of the French bourgeois, nor can the traditional conservatives. Together, they command less than 30 percent of the electorate. The latter is also split down the middle between those who want to align themselves with RN and those who want to align with the centre.

The ENS, for its part, is doing its best to tie the left coalition to itself. It has now proclaimed, with the New Popular Front, a ‘Republican Front’ against the RN, where the ENS withdraws candidates in those constituencies where they have little chance of winning, in favour of the NFP. At the same time, they are pressuring leaders to distance themselves from Mélenchon and France Insoumise; that is, the left of the movement.

It is hard to see how they could make the numbers work, but clearly their idea is to break the more moderate elements away from Mélenchon’s LFI to get them to prop up the centre. This would be completely in keeping with the history of the Communist Party (PCF), the Greens and the Socialist Party (PS). As one of the leaders of the Socialist Party bragged in an interview this week, it was their votes that got Macron into power.

Any ‘Republican Front’ would require LFI to support a new government, since the LFI will control half the NFP seats. Indeed, the FT editorial proposed precisely such a constellation this week. But the ENS refuses to have anything to do with Mélenchon, preferring to work only with their ‘republican’ partners.

LFI has, over the past year, stood out against the other parties of the left. Their opposition to war and imperialism, particularly the war in Gaza, has led the other ‘left’ parties to launch vicious attacks against the party in general and Mélenchon in particular. It is a disgusting spectacle to see the leaders of the PCF and the PS attacking Mélenchon for ‘anti-semitism’ because he opposed Israel’s invasion of Gaza. They themselves have cosied up to Macron on all important foreign policy questions.

This is why the Communists of Révolution opposed the formation of the New Popular Front. The reality is that the rise of the RN has been prepared by the centre: first with the Socialist administration of Hollande, then the ‘lesser-evilism’ of supporting Macron against Le Pen. All of that has prepared the way for the ‘greater evil’.

The Socialists and the Greens tied their fortunes to Macron. Meanwhile, France Insoumise and Mélenchon have tied their fortunes to the Socialists and the Greens. The effect of this is that the massive discontent in French society finds its distorted expression through the one party that has remained in opposition, which is on the far right. For their part, of course, they offer nothing but demagogy, as can be seen with Meloni since her accession to power. The far right, fundamentally, stands for the same rotten programme as Macron. Nonetheless, the behaviour of the leaders of the left, starting with the Socialist Party, the Greens and the Communist Party, has effectively paved the way for the RN.

The programme of the NFP is weaker even than that of the previous 2022 left coalition of NUPES, but still the bourgeois are not happy with it. Its programme includes raising the minimum wage, reversing Macron’s pension reforms, price controls on essential goods, and massive investments. It is a threat to the interest of big business and completely at odds with the latter’s programme of cuts and attacks on workers’ rights. Nonetheless, the chief of the biggest stock exchange group in Europe had these consoling words for the markets:

“‘I can hardly imagine that, in the event one of these two forces [RN and NFP] get into the office, that they will be able to implement everything they promise because of the combination of rating agencies, unions’, pressure from the EU and the president’s power, which would ‘mitigate the impact of any outlier or [inexperienced] party’ doing what they want.” (Business needs to calm down about French election, says Euronext CEO)

Basically, through its institutions, the bourgeoisie can stop the implementation of the NFP programme. Socialist President Francois Hollande won his 2012 presidency promising to tax the rich to stop austerity. He wound up abandoning his programme in favour of tax cuts for corporations and austerity for the working class.

With such precedents, it is no wonder that workers have turned away from the PS and its closest allies, the Greens and the PCF. In the end, it is a political question: when faced with a choice between capitalism and the programme you were elected on, what will you choose? These parties have shown already that their promises are not worth the paper they are written on.

So, it is entirely logical that a layer of the working class is now turning to the RN in sheer exasperation: ‘Maybe, just maybe, they can make a difference.’ Certainly, the other parties haven’t been able to. Le Pen and her PM will only continue Macron’s policies of cuts and austerity, but with added poison and bigotry.

This is abhorrent to the youth, who can see through the demagogy of the far right, but also disdain Macron and his party. 48 percent of 18-24-year-olds voted for the NFP in the first round, and 38 percent of the 25-34 year-olds. RN won amongst middle-aged voters, while Macron is backed by the over-70s. Only 9 percent of 18-24 year olds support ENS.

For a working-class alternative

The youth can see far more clearly than the politicians of the NFP. The centre is finished, and the way forward must be on a class basis, which means a clear break with Macron, and those who are trying to keep him in power.

The crisis of French capitalism is now reflecting itself in a deep political crisis. It seems the only government on the cards is one led by the RN, either that or a continued political crisis, with no government. The whole situation is crying out for a working-class alternative.

Since 2016, there have been several opportunities to topple Macron in the struggle over labour laws, the yellow vests movement, last year’s movement against Macron’s hated pension reform, etc. Had any of these struggles brought the government down, Macron would have faced a challenge from the left, not from the right. Now, the failure of those movements can be capitalised on by Le Pen and the RN.

As Révolution points out, the moderation and timidity of the leadership of the working class is holding back the movement. The comrades are launching the Revolutionary Communist Party for those who are willing to take up that struggle. This an important step to unite the best workers and youth under a common revolutionary banner.