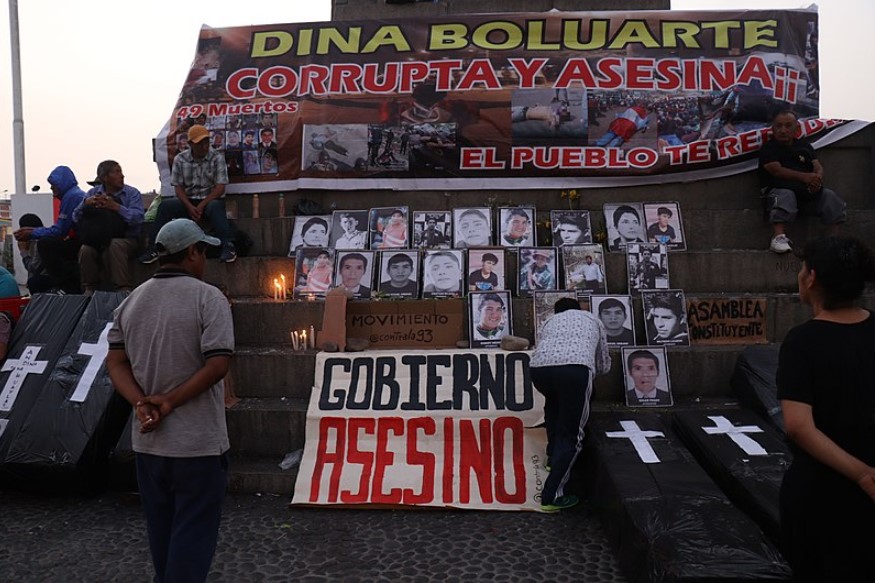

One month after the Dec. 7 coup against Peruvian president Pedro Castillo, the new illegitimate government of Dina Boluarte has used brutal police and army repression to put down protests, leaving 45 dead. Workers and peasants have resisted the coup with mass demonstrations, road blockades, national and regional general strikes and the formation of committees of struggle across the country in a movement that has its epicentre in the poorer, more Indigenous southern departments. Who was behind the Dec. 7 coup and what are the prospects for the mass movement of resistance?

Pedro Castillo was elected in a very close second round of the presidential election in July 2021, as the candidate of the Peru Libre (Free Peru) party, defeating right-wing demagogue Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of former dictator Alberto Fujimori, who was the candidate of the ruling class and the mining multinationals.

Castillo’s campaign, under the slogan “never again poor people in a rich country”, captured the imagination of millions of workers and peasants, particularly in the poorer regions of the country, where the proportion of Indigenous Quechua and Aymara speakers is also higher. In some of the mining districts, he received over 80 percent of the vote. The expectation was that, after decades of extreme liberal capitalist policies in favour of the interests of the big mining multinationals, their power and multi-billion profits were going to be rebalanced in favour of the majority of Peruvians.

Castillo’s program promised to renationalize the Camisea gas field and to renegotiate the mining contracts, which account for the biggest share of the country’s exports and government revenue. Copper and gold are the country’s main mineral products, with contracts in the hands of a handful of U.S., U.K., Canada, China and Mexico-based multinationals.

Castillo threatened that, if multinationals did not agree to renegotiate the contracts, they would be nationalized. This of course raised alarm bells amongst the Peruvian capitalist oligarchy and the multinationals, a compact group of 17 large companies that control the country’s economy, mass media, the state and the main political parties. Despite a campaign of lies, slanders and manipulation, Castillo managed to win the election, the results of which were contested for weeks by Fujimori’s supporters.

Concessions under pressure

The program of Peru Libre, on which Castillo stood, contained a contradiction. Despite the party declaring itself “Marxist, Leninist and Mariateguist”, its platform was not a socialist one based on the expropriation of the means of production, to be used in a democratic plan of production under workers’ control. Rather, it talked about a vague and undefined “peoples’ economy with markets”, calling on the national bourgeoisie to work for the benefit of the majority. That is completely utopian. The capitalist class is only interested in maximizing profits. Any individual capitalist who chooses another path would be quickly put out of business by their competitors.

In a country like Peru, additionally, the local bourgeoisie is subordinated and linked to foreign imperialist multinational interests by a thousand threads. In reality, it is the mining multinationals that rule the country, in collaboration with their local agents in the capitalist oligarchy.

Once elected, Castillo was faced with a very complicated situation, with a hostile parliament in which he was in a small minority. At the time, we warned that he had two options: either base himself on the mass mobilization of the workers and peasants in the streets to deal blows against the ruling class and the multinationals, or be trapped by the very unfavourable balance of forces in the bourgeois institutions and forced to make concessions to the capitalist oligarchy.

Right from the beginning, he chose the second option: concessions and retreats from his own program. He dismissed his foreign minister, Béjar, as he had upset the military high brass by mentioning the role they had played during the dirty war against the Shining Path guerrillas. He then dismissed his prime minister, Bellido, as he was seen as too radical for the capitalist elite. The minister of labour who dared to propose a law against subcontracting (one of the main scourges of the Peruvian working class in the last three decades) was also removed.

Having promised to increase royalties on the mining companies, he then dropped the idea, under pressure. In a visit to the U.S., he reassured foreign multinationals that their investments would be safe. As a public sign of his shedding any radical credentials, he also broke with Peru Libre, which further decreased the size of his own parliamentary group, now split in two. The idea of a Constituent Assembly to re-draft the Constitution, which dates back to Fujimori’s dictatorship, was dropped in the face of lack of parliamentary support for any move in that direction.

However, as it is always the case, every concession he made was seen as a sign of weakness by the rich and powerful, who then proceeded to demand more concessions. At the same time, every concession had the effect of weakening his own base of support. The campaign of attacks through the media, with motions of no confidence in parliament, baseless allegations of corruption and nepotism continued unabated.

Still, the ruling class was never reconciled to Castillo. The workers and poor who had voted for him still saw him as one of their own and were emboldened in their demands. Local communities disrupted mining operations, demanding a share of the profits. An article in Reuters in July 2022 carried the headline “Peru’s mining execs ‘lose faith’ in gov’t despite moderate shift”, which summed up the situation.

Castillo had been elected on the strength of his program, and also of his background—that of a teacher trade unionist who had led a successful national movement, who also had roots in the rondero peasant patrols’ movement. The racist Peruvian oligarchy could not stomach the idea of a man coming from the working-class and poor majority occupying the country’s highest office. Despite his concessions and accommodations, he had to go.

The coup is launched

On Dec. 7 the coup was consummated. Castillo was facing, for the third time, a motion of no confidence in parliament, under the wide-ranging charge of “permanent moral incapacity”, for which no actual proof of any wrongdoing is needed. To preempt the move, he made a national broadcast in which he announced the disbanding of the parliament, which had constantly blocked his initiatives and called for new elections within four months. He also announced the convening of a Constituent Assembly. This was within his powers, but immediately led to a counter-reaction by all the powers of the capitalist state. His own ministers deserted him, the state prosecutor issued an arrest warrant against him, the capitalist media shouted that he had carried out a coup. By the end of the day he had been arrested, parliament had voted for his removal and a new illegitimate president had been sworn in, his deputy Dina Boluarte.

Behind this “constitutional” coup was the bosses’ organization CONFIEP, the mass media, all branches of the state apparatus, the mining multinationals and of course, the US embassy, which hurried to recognize the new illegitimate government.

The presidency of Castillo raises starkly the question of the limits of the so-called “progressive governments” in Latin America. Any attempt to meddle with the interests of the ruling class and the powerful multinationals, which are looting these countries’ resources, will be met with a relentless campaign of destabilization.

The capitalist oligarchy will use all means at their disposal to defend their interests. They will attack any president that threatens them, however mild his or her program might be—up to and including removing them from power. For them, bourgeois democracy is a tool that is useful only as long as the results it produces guarantee their private profits, wealth, and power.

What they had not counted on was the reaction of the masses of workers and peasants. For them, the issue was clear: the president they had elected, Castillo, one of their own, had been removed by the capitalist oligarchy. That could not be allowed, it was an attack on their democratic rights and aspirations. A mass movement started, with road blockades, massive demonstrations and protests across the country.

The movement was growing in intensity, with protesters taking over regional airports and in some cases ransacking the regional and local offices of the judiciary and the state prosecutor. The illegitimate president feared losing control of the situation and reacted by using brutal repression. Faced with a call for a nationwide general strike on Dec. 15, she declared a state of emergency and then imposed a curfew in several of the southern departments where the protests were more intense. Finally, she sent the army against the demonstrators.

In Ayacucho, the masses defied the army and, forcing their way through lines of soldiers armed with weapons of war, marched into the city centre. The death toll quickly escalated to nearly 30 unarmed civilians killed by the army and police. Castillo was remanded in custody for 18 months, longer than he had been allowed to sit in the presidential office for!

Where next for the workers and peasants?

The repression and the arrival of Christmas forced a pause in the movement. This was used to discuss strategy and strengthen its organization. A meeting of representatives of workers and peasant organizations from the southern departments agreed to call an all-out strike in the whole of the region and the formation of joint strike committees. The meeting called for the movement to spread to the rest of the country and announced a “Marcha de los Cuatro Suyos”—a march on Lima with the same name as the huge national march in 2000 that brought down Fujimori.

The renewed strike movement was met again with brutal state repression, using the state of emergency powers, which remain in place. Jan. 9 saw another massacre, this time in Juliaca, Puno, where the police opened fire on the Aymara-speaking protesters which had gathered from the rural districts, killing at least 18, including a minor and a junior doctor who was helping the victims.

The demands of the movement are clear: freedom for Castillo, the closing down of the coup-plotting corrupt congress, ousting of murderous “president” Boluarte, new elections and a constituent assembly.

These are basic democratic demands against the coup. But the workers and peasants already understand that new elections, in and of themselves, would not solve the problem. The whole of the political system is rotten to the core and skewed towards the interests of the ruling class.

In fact, what the mass resistance movement has put on the table is: who rules the country—is it the working-class majority, workers, peasants, students, the women, the Indigenous peoples or is it the unelected and unaccountable capitalist oligarchy, the army, the owners of the mass media and the mining multinationals.

The question of the Constituent Assembly, in the eyes of the masses of workers and peasants, represents precisely that, a root and branch reorganization of political power and a chance for the working class majority to impose their own rules. However, we need to warn that a Constituent Assembly, that is a reform of the political structures, would not solve the fundamental problems that affect workers and peasants in Peru.

Several other countries in the region have had constituent assemblies in the recent past, including Bolivia and Ecuador, and the ruling class in those countries still has their economic power intact. At some point, if the movement is strong enough and threatens to brush aside the ruling class as a whole, a Constituent Assembly of some sort might be conceded, in order to derail the insurrectionary movement of the masses along safer bourgeois constitutional channels. This is exactly what happened in Chile with disastrous results. The 2006 Constituent Assembly in Bolivia played the same role, providing a constitutional way out to the 2005 revolutionary movement during the gas wars.

In struggling for democratic demands, revolutionary Marxists point out the need to deal with the question of who controls the economy and the country’s resources. That means not just changing the Fujimori constitution but actually expropriating the 17 groups that control the country’s economy as well as the mining multinationals. Only by putting the wealth of the country in the hands of the working people can the slogan “never again poor people in a rich country” be carried out into practice.

For the movement to be victorious, the general strike needs to be widened nationally. The comrades of the IMT in Peru are calling for a National Revolutionary Assembly of Workers and Peasants, with delegates elected with the right of recall from every workplace, working-class neighbourhood and peasant community to take the reins of the country. The agreements arrived at the meeting of worker and peasant representatives from the south point in the right direction. The masses have responded heroically despite murderous repression.

It is the duty of the international labour movement to organize solidarity with the heroic resistance of the Peruvian workers and peasants which is an inspiration to us all.