The events of the last weekend in Russia have given rise to all sorts of speculation. On Friday evening, the head of the Wagner mercenary army, the oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, launched a “march for justice” with the stated aim of removing the head of the Armed Forces and the Minister of Defence. By Saturday, he had taken control of Rostov-on-Don and was marching with a heavily-armed column towards Moscow. Putin denounced him as a traitor and promised those involved would be dealt with accordingly. However, by the end of the day, suddenly, Prigozhin’s column turned back and a deal was announced, brokered by Belarusian President Lukashenko. The motivation behind the actions of the different actors is shrouded in mystery, but these events reveal something about the character of Russia’s war in Ukraine and of Putin’s regime itself.

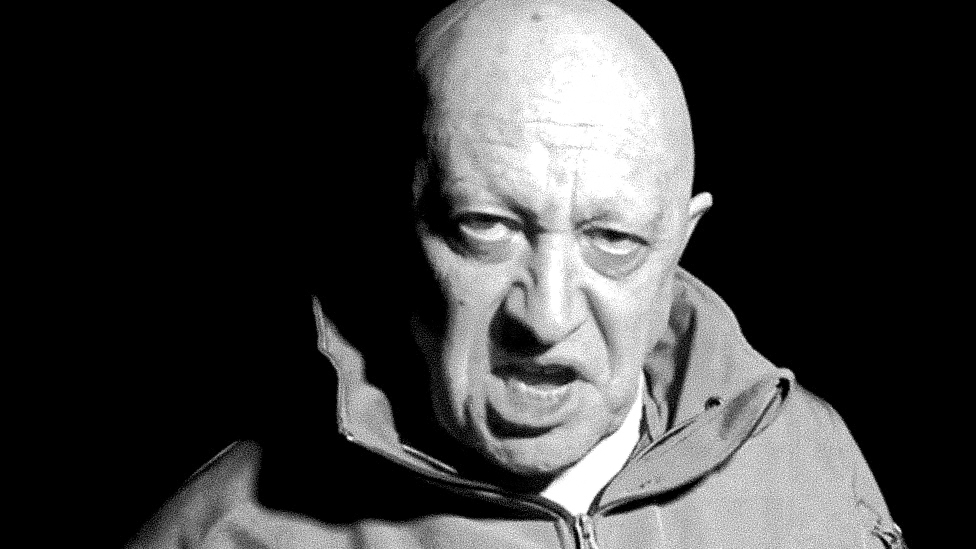

Rather than engage in empty speculation, let us first concentrate on the known facts. On Friday, 23 June, Prigozhin released a series of provocative videos on Telegram, in which he questioned the motives for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: saying it was unnecessary, that Russia was not under threat from Ukraine and that Russia should have reached an agreement with President Volodymyr Zelensky when he came to power. “The war wasn’t needed to return Russian citizens to our bosom, nor to demilitarise or denazify Ukraine. The war was needed so that a bunch of animals could simply exult in glory,” he said. This was, of course, the exact opposite of what Prigozhin himself had said at the time of the beginning of Russia’s invasion, which he was enthusiastic about.

He also launched yet another attack on the Minister of Defence Sergei Shoigu, and the head of the Russian Armed Forces Valery Gerasimov for their conduct of the war in Ukraine, and demanded that they should be removed. “Wagner’s commanders have come to a decision,” he said. “The evil being spread by the country’s military leadership must be stopped.” He then announced that Wagner fighters were going to take over Rostov and that anyone attempting to stop them “would be destroyed”.

This was a serious challenge, one that the Russian authorities were quick to describe as an attempted coup, announcing that they were opening criminal investigations against Prigozhin for “armed rebellion”. He responded by saying: “This is not a military coup, but a march of justice,” in an attempt to appeal to the ranks and officers of the army.

Brewing tensions come to the fore

Source: Presidential Press and Information Office, Wikimedia Commons

This was not the first time Prigozhin had attacked the army leadership. For months there had been tensions, with allegations by the Wagner chief that his troops were not given enough ammunition and other supplies to carry out the war. There was also a constant conflict over who should take credit for advances in the front, particularly in the long battle for Bakhmut in which Wagner’s mercenaries (many recruited from Russian jails) played a key role.

This seems to have been the key issue. At a certain point in the war in Ukraine, when things did not go to plan and Putin was not keen to resort to full mobilisation for fear of the potential political fallout, he decided to rely on the forces of Wagner, a Private Military Contractor (a fancy name for a mercenary company) run by his friend and oligarch Prigozhin. Wagner forces were already being used by Russia in Africa – and previously in Syria – in order to extend its spheres of influence, by offering the services of these mercenaries to different African governments. This is part of a more general trend we have seen towards the contracting out of certain aspects of war to private companies. The United States has spent billions of dollars in hiring the services of PMCs (such as scandal-ridden Blackwater), which have provided tens of thousands of men and women for the imperialist wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, amongst others.

The use of Wagner PMC in the Ukraine War was a very profitable enterprise for Prigozhin, who used the conflict not only to line his own pockets but to build his own power base and project his image through an army of hired bloggers and telegram group ‘military analysts’. This led him to come into conflict with the army leadership.

Once the battle for Bakhmut was over, the army leadership thought it was the right time to move against Wagner. A decision was made that all Wagner operatives who wanted to continue fighting in Ukraine were to sign individual contracts with the Ministry of Defence. That spelled the end for Prigozhin’s lucrative business in this particular war, but also represented a serious setback to the political ambitions he had developed. He declared that none of his men were going to sign such contracts.

Putin, who until that point had been balancing between Shoigu and Prigozhin, in a typical Bonapartist fashion, publicly backed this decision in a big blow to his mercenary oligarch friend. One thing a Bonaparte cannot allow is anyone with ambitions undermining his own power.

Prigozhin now had only two options: abide by the demand and see the end of Wagner’s participation in the Ukraine War, or defy the decision with a show of strength and try to get a better deal from Putin. This also explains his recent comments about alleged successes of the Ukrainian counter-offensive. He wanted to give the impression that his own fighters, a sizable, experienced, battle-hardened core, were indispensable at the front.

In the early hours of Saturday 24 June, his forces had taken several key military buildings in Rostov, including the headquarters of the army’s Southern Military District and the airfield, without firing a shot. In a video posted on Telegram, Prigozhin was seen at the headquarters, talking to Deputy Defence Minister Yevkurov and Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Federation Alekseev.

In another video, posted at 7.30am, Prigozhin demanded that Defense Minister Shoigu and Chief of the Russian General Staff Gerasimov be “handed over” to him, otherwise he threatened to “go to Moscow.”

By 10am, Putin made a televised speech. “Actions that split our unity are a stab in the back of our country and our people,” he said, adding: “And our actions to defend the fatherland from such a threat will be brutal… Those who prepared the military mutiny, who raised weapons against combat brothers, have betrayed Russia, and will pay for this.”

At the same time as leaving no-one in any doubt as to his position, he was also appealing to the ranks of Wagner by describing them as “heroes who liberated Soledar and Artemivsk, towns and cities of the Donbas. They fought and were giving lives to Novorossiya and the unity of the Russian world. Their name and glory were also betrayed by those who are trying to organise the mutiny”.

Significantly, Putin compared the situation with that of 1917:

“Exactly a strike like this was dealt in 1917 when the country was in WW1, but its victory was stolen. Intrigues, and arguments behind the army’s back turned out to be the greatest catastrophe, destruction of the army and the state, loss of huge territories, resulting in a tragedy and a civil war.”

This is of course false, it was the disaster of WW1 that triggered the 1917 February Revolution, not the other way round. But it confirms the reactionary pro-Czarist imperialist nature of Putin’s ideology. That should be clear to everyone (he also attacked Lenin and the Bolsheviks for having artificially created Ukraine when justifying its invasion over a year ago). But that hasn’t stopped the ‘Communist’ Party of the Russian Federation and various other ‘Communist’ parties shamefully backing Putin or having illusions about the ‘progressive’ nature of his regime and the war in Ukraine.

Desperate, defeated adventure

Having thrown down the gauntlet and been rebuffed by Putin, Prigozhin had no other alternative than to desperately launch himself into an adventure. He was probably calculating – or at least hoping – that he had wider support amongst the ranks of the army, amongst officers in high ranking positions and generally within the structure of the state and political power.

His column of a few thousand heavily armed men advanced quickly in the direction of Moscow during the day. Rather than strengthening their positions in the towns and cities they passed, they seemed to be on a mad dash to reach Moscow before the Russian army had time to organise the defence and stop them.

What were his intentions? The Financial Times’ Max Seddon quotes someone he describes as having “known the warlord since the early 1990s” to speculate about Prigozhin’s aims:

“I don’t think he had anything particular in mind. He just decided to go and convince Putin that he should get to keep all the money they took away from him… Then the situation got completely out of control. At some point he realised he didn’t know what to do next. You get to Moscow, and then what? You open the doors of a dozen prisons, some unimaginable freaks come out, the country goes to shit, and then you get to the Kremlin… and you don’t know what to do.”

That seems plausible. Up until that point, there seemed to have been very little in the way of armed clashes. The only resistance Prigozhin faced was an attack from the airforce, which Wagner repelled, downing several attack helicopters. By the end of the afternoon, Wagner’s column had reached Elets, in the Lipetsk region, just 250 miles from the capital Moscow. Speed and surprise had been on their side up until that point.

This can be explained because the military leadership did not want to redirect any forces from and therefore weaken the front, in case the Ukrainian army attempted to take advantage of the situation. And also because the poorly armed and less experienced conscripts along the road to Moscow were not in any mood to face up to a heavily armed column of battle-hardened mercenaries.

By the end of the day, however, Chechen troops had arrived and were surrounding Rostov-on-Don, and military defences had been erected at the entrances to Moscow.

Source: Presidential Executive Office of Russia, Wikimedia Commons

Then there was yet another sudden twist. At 8:30pm Belarussian media announced that a deal had been brokered by President Lukashenko, and Prigozhin announced that “having reached a point where there was going to be bloodshed”, his forces were turning back, away from the capital.

The terms of the agreement, as announced by presidential spokesperson Peskov, mean that Wagner mercenaries that had not participated in the armed rebellion would be allowed to sign up for the army in Ukraine, while those who had participated would not be prosecuted on “account of their military merit”. Moreover, a criminal investigation against Prigozhin was going to be dropped and he would be offered safe passage to Belarus. By 11pm, Wagner’s forces and Prigozhin himself left Rostov-on-Don.

In effect, the original intention, which was to remove Wagner from the Ukrainian war, or at least to subordinate it to the Army command, had been achieved and the armed rebellion diffused with hardly any loss of life. Prigozhin had no other alternative other than to accept this deal. He had not managed to rally any support for his bid and he was aware that he had no chance of actually winning in an open military conflict with the army, even if he managed to reach Moscow. He had at least saved his life and perhaps been offered the possibility of keeping his assets and Wagner’s lucrative operations in Africa.

In any case, there is no honour among thieves, and now that Prigozhin has laid down his weapons, his position has become much weaker. Already on the morning of Monday, 26 June, Russian media reported that “the criminal case on organising an armed rebellion, the main defendant of which is Prigozhin, has not been terminated and continues to be investigated by an investigator from the investigative department of the FSB”.

As some have commented, if there is one thing a Bonapartist leader like Putin cannot forgive, that is betrayal. Prigozhin may now find it very difficult to take out any life insurance policy!

Threat neutralised, but cracks remain

It is clear that, in the attempt to hold the line in the Ukraine war, Putin had taken a big gamble in using mercenary forces that are not directly under his control or chain of command. The state had partially lost the monopoly of violence. And this is not just the case with Wagner. The state-owned energy company Gazprom has also been allowed to create its own armed militia.

But Prigozhin had become full of himself and was developing ambitions as a result. This threat had to be eliminated. In launching his open defiance of Putin, Prigozhin did not find the support he thought he could count on, and he has now been neutralised as a threat. If, as seems the case so far, Shoigu and Gerasimov remain in their jobs, then Prigozhin’s defeat will be complete and he has merely strengthened his rivals.

Of course, as the Russian comrades of the IMT pointed out in their statement, there was nothing to choose from, from the point of view of the Russian working people, between Putin and Prigozhin. This was a quarrel between a reactionary oligarch and the head of a reactionary oligarchic regime, the content of which was the struggle for the loot and the relative distribution of power.

It is ironic that Western imperialist commentators were gloating about the possibility of a successful coup by Prigozhin, a reactionary mercenary. The more sober-minded representatives of the ruling class were a bit more wary. The Financial Times editorial commented: “The weekend’s unrest serves as a reminder, too, that if Putin is ever toppled, it could be by more hardline elements determined to prosecute the war in Ukraine in still more vicious fashion.“

The Western bourgeois media was full of all kinds of speculation, that this was the end of Putin, an imminent collapse of Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine, and so on. In fact, both Western intelligence and the Ukraine high command have commented that no gaps emerged in the Russian line of defence during these events.

During events such as these, it is advisable not to be influenced by idle speculation and to stick to what is actually known. It is also advisable to be patient and wait for the facts to emerge.

So far, the oligarchs that count have lined up behind Putin. No section of the army officer caste came out in favour of Prigozhin and he did not get any support from the population. The only real concrete result is that the Wagner group, and Prigozhin in particular, have been removed as a direct threat to Putin, which is what Putin was working towards.

Does this mean that is all is well with the Putin regime? No, it does not. What the Prigozhin adventure reveals is that there are cracks in the regime. For now these will be papered over and Putin will rally the forces around the need to unite in defence of the “fatherland”. The relatively quick end of Progozhin’s adventure will send a signal to anyone who may have been thinking of supporting him.

However, in the long run, what today may seem a small crack can widen. Then the scenario – after further fighting in Ukraine, with more young men being butchered – can change radically, and the memory of 1917 really could come back to haunt Putin. Not in the caricatured manner that he has presented it in relation to Prigozhin, but as a real workers’ revolution that would sweep away the oligarchs and the regime that represents them.