The following article was first published on August 4, on marxist.com. At the current time, the situation is still ongoing, and ECOWAS is still threatening Niger with military intervention.

As reported previously, the recent coup in Niger and the response from surrounding West African states is intensifying the rising tensions and political instability in the region.

On July 30, the ECOWAS bloc of West African states, currently headed by Nigerian president, Bola Tinubu, announced sanctions against the military junta that seized power in Niger on July 26. Further, ECOWAS delivered an ultimatum, threatening military intervention if the deposed government of Mohamed Bazoum is not restored by the end of this week.

This represents a much-firmer line from ECOWAS, which had been more restrained in its response to recent coups in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso. So far, however, its intervention has intensified the instability in the region, which now threatens to spread further.

The announcement of ECOWAS’ ultimatum was met with an opposing threat from the military governments of Mali and Burkina Faso, which have both evicted French forces from their borders and openly aligned with Russia internationally. On July 31 they warned that any military intervention in Niger would be treated as a “declaration of war” against their countries as well, raising the potential for a war involving the bulk of West Africa. Guinea has also confirmed that it would support the military government in Niger.

Since then, ECOWAS has continued to ramp up sanctions against Niger, stopping all trade and cutting off the supply of electricity from their countries. But the effect, as yet, has only been to stiffen the resolve of the junta in Niger, which has shown no sign of backing down.

On Aug. 3, which marked 63 years since Niger won independence from France, a delegation from ECOWAS returned home without having achieved any diplomatic solution to the crisis. Meanwhile, thousands of pro-government demonstrators attended a rally in Niamey’s Independence Square, shouting slogans, including, “Down with France!” and, “Long live Russia!”

Social and economic demands also mingled with expressions of anti-French or pro-Russian sentiment. The demonstration was supported and mobilised for by the ‘M62 movement’, which was formed last year in protest against the rising cost of living and corruption scandals involving the government. As one demonstrator, Oumar, put it:

“I have no job after studying in this country because of the regime France supports… All that has to go!”

This sentiment is evidently not confined to Niger, nor to Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso, which have each experienced several coups in the last 3 years, amidst deep social and political instability.

Senegal

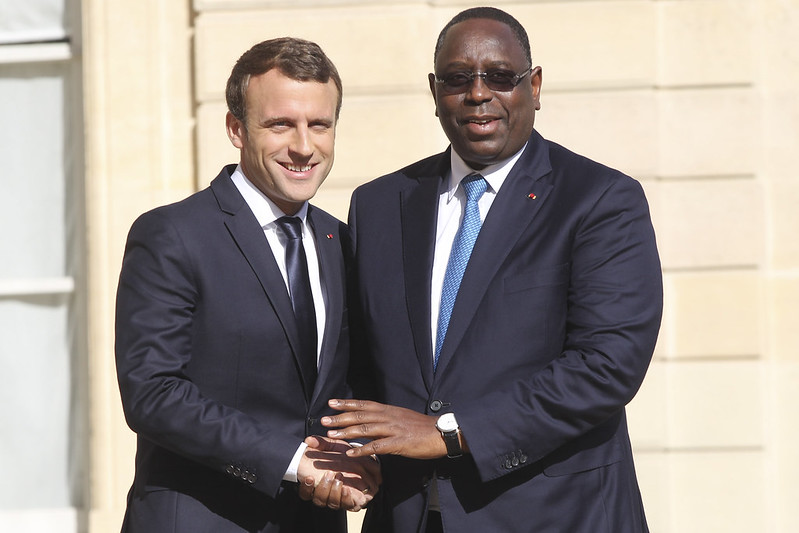

There is now a very real risk that the growing instability in the Sahel will strike next at the government of Macky Sall in Senegal, which had been described by the The Economist as a “beacon of stability and democracy in a region beset by coups and overstaying presidents”.

Senegal’s Foreign Minister, Aissata Tall Sall, announced yesterday that his government would send troops to intervene in Niger, in accordance with ECOWAS’ decision, should Sunday’s deadline pass unheeded. The recent overthrow of Bazoum in Niger was “one coup too many”, according to Tall Sall.

But recent events suggest that the rulers of Senegal are less worried about coups abroad than they are about revolutions at home. On Monday, Senegal’s main opposition party, PASTEF, was officially banned and its leader arrested on charges of stoking violence and “plotting an insurrection”.

This move represents an intensification of a bitter political struggle that has been developing since mass protests erupted across the country in June over high youth unemployment and the systematic corruption that blights West Africa’s “most stable democracy”. As one 22-year-old protestor, interviewed in The Guardian put it:

“There is no justice here… because we’re living in a dictatorship. I’m crying inside. My heart is bruised.”

This mood of frustration has been brewing since 2012, when the youth evicted Abdoulaye Wade from power. Ten years on, the crisis faced by the Senegalese masses, and the youth in particular, has only worsened under Macky Sall, leading to fresh outbreaks of mass anger.

Ousmane Sonko, the leader of PASTEF, has been under house arrest since May and was convicted in absentia of sexually assaulting a person under 21 in 2021, a charge which Sonko has consistently denied. Following his conviction Sonko was sentenced to two years imprisonment, which – conveniently for the government – would have rendered him ineligible to stand in presidential elections next year. Until the end of July, he had been serving his sentence at home. He remains in custody.

Since Sonko’s latest arrest, a new wave of street protests have erupted across Senegal. Pro-Russian social media accounts have been posting videos of protestors burning French flags, but it is unclear when or where these videos have been taken. Nevertheless, the potential exists for the anti-French slogans, that have been clearly on display throughout the Sahel, to find an echo in Senegal, which is an important French ally in the region.

Unable to quell the mass protests, which have continued since Monday, this “beacon of stability and democracy” banned the social media app TikTok yesterday. The reason given by the government for this further act of repression was that the app was being used to “spread hateful and subversive messages threatening the stability of the country”.

However, as can be seen many times in history, attempts by the state to suppress the masses can often spur the movement on, and so far the banning of TikTok does not appear to have stabilised the situation in Senegal.

Evidently, the regime in Dakar, and its masters in Paris, would like to see firm action to reverse the coup in Niger, in the hope that the genie of mass unrest and political instability can be put back in its bottle. But ironically, just as the government’s attempts to repress the movement at home have only provoked the movement, a further escalation of conflict with Niger and its supporters in the region could have an enormously destabilising impact at home.

Nigeria

This consideration will not be far from the mind of Nigerian President Bola Tinubu, whose government is perched atop a giant powder keg. Vast oil reserves and powerful industries make Nigeria the largest economy in Africa. Nevertheless, the country remains the “poverty capital of the world.” Consequently, mass dissatisfaction is rife and like its neighbour, Niger, Nigeria is facing its own Islamist insurgency in the North East, in the form of Boko Haram, which it has been unable to displace after roughly 10 years of conflict.

Furthermore, one of the first acts of the Tinubu government has been to cut a popular fuel subsidy in order to “save our country from going under”. This measure has already met with opposition from the Nigerian labour movement.

It should not be difficult to recall that one of the most important triggers for the revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt, and more recently Sudan, have been precisely cuts to subsidies that the masses had relied upon for things like food staples and fuel. The fact that Tinubu is taking this measure clearly shows the deep crisis facing Nigerian capitalism, and the social instability that looms over the country.

Any military intervention in Niger would carry a huge risk of provoking social explosions inside Nigeria. Such a prospect would carry huge significance for the whole of Africa. Thus far, the coups and counter-coups that have rocked the region have largely taken place in extremely poor, undeveloped countries with an overwhelmingly peasant population.

The reason why the instability in these countries has expressed itself as coups and counter-coups is primarily because of the extreme weakness of the local bourgeoisie, which is not only tiny, but tied hand and foot to foreign imperialism. Therefore the state tends to take on greater prominence.

Further, the small size of the working class in these countries, and the absence of revolutionary leadership, has created a deadlock in which the emergence of Bonapartist regimes is almost inevitable. What is particularly interesting in the present situation is the phenomenon of a layer of junior officers taking power instead of the generals, reflecting the anger from below. The case of Ibrahim Traore, a 34-year-old captain in Burkina Faso, is a case in point.

Nigeria, by contrast, is the largest economy in Africa and by far the largest and most powerful economy in the region. It also possesses one of the largest working classes in Africa. Should the present crisis provoke a mass movement of the Nigerian working class, this could dramatically transform the situation.

Painful dilemma

Therefore, the attempt by the West’s allies in the region to reassert control over the situation in Niger presents a painful dilemma for Tinubu, Sall, and other ECOWAS leaders. If they sit on their hands after making such bold threats, such a humiliating climbdown could encourage further instability whilst tarnishing the prestige of their own regimes.

On the other hand, carrying out their threats could just as easily trigger instability and social unrest, whilst also risking lighting the fuse on a conflict that could easily spiral outside anyone’s control. Meanwhile, with its nose already bloodied and its hands tied up in Ukraine, it is unlikely that the West would pour military support into the region.

Most likely, both sides will attempt to adopt as hard a posture as they can, ramping up sanctions and diplomatic pressure, whilst holding back from a military clash. Whether they are able to hold back the situation however is not wholly up to them.

What is certain is that further explosive events are on the order of the day, which Marxists should watch very closely in the coming weeks and months.