In Hwang Dong-Hyuk’s massively popular fictional TV series Squid Game, debt-ridden contestants risk their lives for a chance to make a massive fortune in a competition where losers face death.

Beyond the brilliant acting and graphic violence, Squid Game reflects the real horrors of capitalism and its death agonies. No wonder it has attracted huge viewing figures and considerable media interest even in the British press.

In this chart-topping Netflix series (currently number one in over 90 countries), we see hundreds of impoverished Koreans compete in a series of deadly playground games to win a £30 million cash prize. United by their suffering under capitalism, the series tracks their miserable lives and their utter desperation to win.

Desperate

The show starts by introducing the main character, Seong Gi-Hun, as he negotiates a miserable life of gambling debts and strained family ties. When a stranger invites him to take part in a competition with a very large prize as a reward, the offer seems too good to refuse.

Each brutal round of the game creates (artificial) scarcity to drive the participants towards more ever more desperate measures.

Food is unfairly distributed, violence is condoned, betrayal is rewarded. Divisions fester into bigotry as contestants eschew solidarity based on race, gender, age. Marx’s words ring true: ‘where want is generalised, all the old crap would revive’.

The players are free to leave the competition, if a majority vote to do so. Yet this freedom is an illusion, much like bourgeois democracy.

Offered the chance to return to their usual lives, the contestants are faced with the inescapable, grim reality of their existence. As one character dejectedly puts it, life is “just as bad out there as it is in here”.

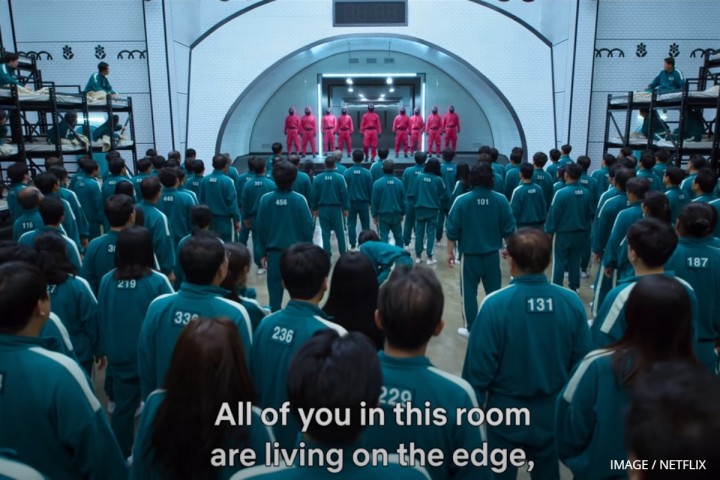

Rules are enforced by a rigid hierarchy of armed bodies of masked men. They maintain a complete monopoly on violence, using pistols and machine guns to execute those players who break the rules and those who have lost a round. The parallels with the security apparatus of the Korean ruling class are difficult to ignore.

But the similarities between fiction and reality are no coincidence. As director Hwang Dong-Hyuk put it: “I wanted to write a story that was an allegory or fable about modern capitalist society, something that depicts an extreme competition, somewhat like the extreme competition of life.”

Beyond the screen

Squid Game joins a growing collection of Korean social realism, with films like The Host and Parasite also exposing class exploitation in South Korea. Despite its surreal themes, Squid Game is not too far removed from the gruelling material conditions facing South Korean workers in real life.

2020 brought South Korea’s worst unemployment crisis since 1997. Exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, South Korea has seen over a decade of steady decline in employment. Amongst the youth, the figure stands at 9.5 per cent. It’s little wonder that Korean youth have taken to calling their homeland “Hell Korea”.

Old age and retirement offer no hope for South Korean youth and workers. While the UK ‘only’ has 15% of people aged over 66 living in poverty, 43% of the older South Korean population face poverty. With an aging population, and deaths outnumbering births, the elderly have become another downtrodden layer under capitalism.

Shackled by debt

For each of the Squid Game contestants, the large cash prize offers an escape from their debt bondage. In reality, South Korean household debt has sky-rocketed, with the average household debt-to-disposable-income ratio sitting at 191%. In total, household debt is an astronomical $1.54 trillion.

While the fictional contestants of Squid Game and workers in the real world suffer the consequences of their debt, the South Korean government can find no better solution than to add to their own national debt with stimulus packages. In 2019, the national debt stood at $726 billion, which is predicted to hit $1 trillion by next year.

Imperialism

Towards the end of the series, we are introduced (spoiler alert!) to the VIP guests who fund the Squid Game. While the contestants and game’s staff are Korean, these wealthy observers mostly have American accents.

As in The Host, the American VIPs in Squid Game are indifferent to the suffering of the Korean characters, prioritising material gain over any sense of morality.

In the real world, the US continues to use the Korean working class as pawns in their imperialist games. At the time of writing this article, North Korea is attempting to broker peace with their southern neighbours. At the same time, South Korea flexes its US-supported military muscle with a new submarine-launched ballistic missile.

Power in numbers

While the Korean working class suffer under the dual oppression of the Korean capitalist class, composed of chaebols (Korean industrial conglomerates run by wealthy dynasties), and US imperialism, their history is one of militancy.

In 2015, South Korea saw a wave of three general strikes. Led by the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), tens of thousands of workers took to the streets to protest against right-wing President Park Geun-Hye and her anti-worker laws.

In response, the state launched mass repression, with police brutality and targeted arrests of trade union leaders. Although the laws were passed with minor adjustments, the Korean working class drew important lessons from the struggle.

This month, the KCTU is mobilising for a new general strike on October 20th to express their anger against the exploitative system. To promote the strike, The KCTU has created their own advertisement in the style of Squid Game called “General Strike Game.”

Revolution

It is clear that global class consciousness is growing, driven by worsening material conditions.

The suffering of Seong Gi-Hun and his fellow debt-ridden players in Squid Game is not restricted to the small screen, nor to South Korea itself. There is no solution under capitalism, any more than there is through blood-drenched games.

For the Korean working class, the task is that of revolution. A united working class movement united around concrete, socialist demands, with support from the KCTU and other workers’ organisations, could kick out the bosses and the imperialists, and bring the chaebols and the rest of the bosses’ system under worker control.