At a quarter past midnight last night, I received a telephone call from Mexico with news that had a profound effect upon me. I was told that my old friend and comrade Esteban Volkov was no more. While I cannot say that this news was entirely unexpected, since Esteban had reached the ripe old age of 97 in March, it nevertheless filled me with a profound sense of irreversible loss, not only of a very dear friend, but of the last remaining physical link with one of the greatest revolutionaries of all times, Leon Trotsky.

I must make it clear from the outset that I am not a sentimental man, nor do I believe in icons, either of the religious or political kind. Having said that, one must accept as a fact that symbols play an important role in life in general, and also in politics.

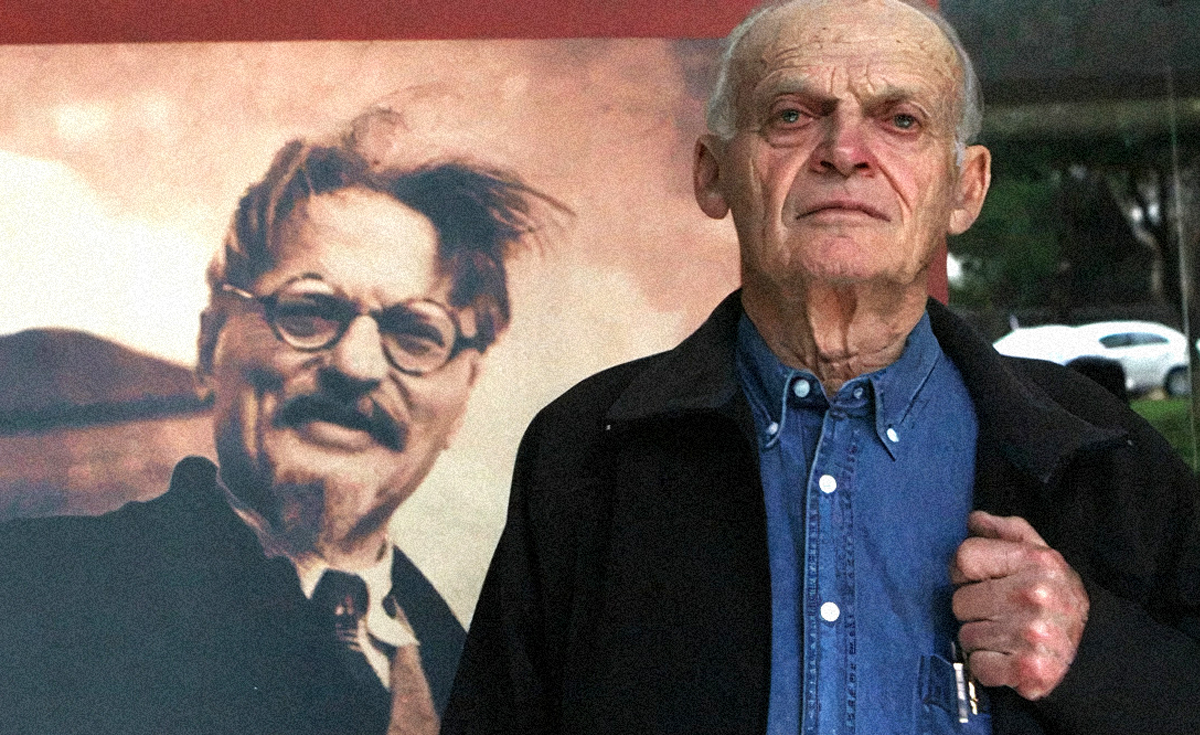

Esteban Volkov was an important living symbol – the symbol of a whole revolutionary epoch, a heroic period of storm and stress, full of triumphs and tragedies, which affected the lives of millions of people and therefore of individuals. And perhaps nowhere is this fact more evident than in the family of Leon Trotsky and of Esteban Volkov.

I have known Esteban for a period of approximately 34 years. Our first actual meeting was in the year 1989 in Mexico City, and it marked the beginning of what became a deep and lasting friendship, based not only on personal affinities but above all on a fundamental political solidarity.

My first impression of Esteban as a person was of a very friendly, kind and affable character. He was always ready with a joke, always smiling and laughing. But I did notice something from the beginning which made a deep impression on me. He had blue eyes, which struck me as being a very Russian trait. But it seemed to me that somewhere behind these smiling eyes there lay a deep sense of melancholy and an intense suffering, which was evident even though he clearly never intended to show it.

source: Museo Casa de León Trotsky

The reason for this soon became clear to me. He said to me when he was in his early 60s, and repeated the point many times thereafter: “I am the member of my family who has lived the longest.” These words were very true. But before we deal with this question (which I can only sketch very roughly because of physical constraints, which I will explain) I must tell you why his name is Volkov and not Bronstein or Trotsky.

He did not bear the name of his illustrious grandfather. But then, the name of Trotsky itself had an entirely accidental character, being taken from one of Trotsky’s jailers in Tsarist times and used for the purposes of underground work as a pseudonym.

Trotsky was married twice; the first marriage was in Siberia where he was exiled in the early years. This marriage resulted in two daughters, one of whom, Zinaida, was Volkov’s mother. His father, Platon Volkov, had been an active Bolshevik revolutionist who was arrested by Stalin for his participation in Trotsky’s Left Opposition in the 1920s. He disappeared into Stalin’s gulag, where he was later murdered.

I learned from Esteban (whose actual name was Vsievolod, or Sieva Volkov) that he had absolutely no memory of his father. It was only many years later that I saw an old blurry photograph of Platon Volkov that someone had sent to the Trotsky Museum in Mexico. To the best of my knowledge, this faded photograph was the last remaining evidence of his existence.

In 1927, Stalin had Trotsky expelled from the Russian Communist Party and exiled, first to Almaty in Kazakhstan, and then to Turkey, where he took up residence on the island of Prinkipo. When Esteban’s mother Zinaida asked for permission to visit Trotsky in Prinkipo, permission was given, but Stalin only allowed her to take her young son Sieva with her, leaving behind her little daughter who was still a baby, while her husband remained in prison. But as soon as Zinaida had left the country, Stalin ordered that her Soviet citizenship be cancelled. This was a devastating blow delivered against a person who was already suffering from severe mental trauma, and it sealed her fate. Trotsky sent her to Berlin to receive treatment from a doctor who practised in the new field of psychoanalysis. But it was already too late. She succumbed to depression and committed suicide by putting her head in a gas oven. Sieva was thus left without a parent in a foreign country, which moreover was now engulfed by the brown tide of Nazism: a frightening prospect for any child.

Trotsky had two sons by his second marriage with Natalia Sedova. The youngest was Sergey, who chose to remain in the Soviet Union, and, not being politically active, was thought to be safe. That was a big mistake. Stalin’s sadistic thirst for vengeance was satiated not just against his immediate enemies, but against their entire families. Sergey was arrested and murdered in a concentration camp. But that came later.

At the time of Zinaida’s death, Leon Sedov, Trotsky’s elder son, was active in the leadership of the International Left Opposition in Berlin. After the victory of Hitler, he moved to Paris to establish a centre of the International in that city, taking Sieva with him.

The thing that struck me most about Esteban Volkov was the irrepressible nature of his character. The trials and tribulations of his young life would have been more than sufficient to psychologically destroy any child. But not so Esteban Volkov. He often related to me with great pleasure the memories of his stay in Paris, where he wandered freely, exploring, and having adventures along the banks of the Seine. But these pleasures were not to last for any length of time. The long arm of the GPU extended to Paris and far beyond. Leon Sedov was murdered while recovering from an operation in hospital. Once again, Esteban Volkov was, in effect, orphaned.

A further trauma began when the female partner of Leon Sedov, a highly unbalanced individual, claimed custody over the child and vigorously contested the attempts of his grandfather to bring him to Mexico, the only country which had afforded Trotsky political exile. In the end, Trotsky won his case, and Sieva Volkov was allowed to leave to join his grandfather in Coyoacán on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Incidentally, there is a very touching letter which Trotsky wrote to Sieva at that time, imploring him not to forget the Russian language. His grandfather argued that Sieva had a little sister in Russia and sooner or later might meet her again, and therefore he should be able to communicate with her. As a matter of fact, Zinaida’s mother, Aleksandra Sokolovskaya, had been arrested by Stalin and sent to a gulag where she died. Esteban’s little sister disappeared and for a long time was assumed to be dead. Many years later, however, through the investigations of the French Trotskyist Pierre Broué, she was found alive in Moscow, and in the Gorbachev years, Esteban was able to visit her. But this is a tragic meeting, for two reasons. Firstly, as Trotsky had predicted, they were unable to communicate with each other in a language they both could understand. Furthermore, she was in the final stages of cancer, and died shortly afterwards.

For a time in Coyoacán, Sieva discovered the joys of a family life for the first time. “It was like a little family”, he would say. His grandfather treated him with all the care and attention and love which he had lacked. His account of Trotsky’s kindness and love gives the lie to the oft-repeated slander that Trotsky was a cruel, hard-hearted tyrant. I will not say more on the subject now, as I have dealt with it previously and will doubtlessly deal with it again.

This idyllic period in Coyoacán was like a peaceful harbour between two terrible storms. And the most terrible one was yet to come. The GPU made two attacks on the Trotsky household. In the first one, Esteban was wounded in the foot by a stray bullet. But the attack failed in its objective, which was achieved a few months later in August 1940. Esteban was only 14.

I will not repeat what has been said about this bloody event. It has been related many times by Esteban Volkov himself, but each time I noticed one thing: when Esteban repeated this story, he seemed to be reliving the events of that terrible day, as if they had happened only yesterday.

I had no doubt that when Stalin heard the news of the successful assassination, he would have been overjoyed. He would have concluded “mission accomplished”. However, he was mistaken. It is not a difficult thing to end the life of a man or a woman. We are very weak animals and anything can kill us: a knife, a bullet, or an ice-pick. But it is impossible to kill an idea whose time has come.

The struggle that Trotsky began to defend the heritage of Lenin and the October Revolution did not end with the assassination of Trotsky. It has continued and still continues to this day. And a very important role in that struggle has been that of Esteban Volkov, who dedicated his entire life to defending the ideas of Trotsky and what he used to call “the historical memory”. The clearest expression of this was his tireless work to establish and defend the Trotsky House Museum in Coyoacán, which is an important point of reference for our movement internationally.

His work in the Museum is being loyally continued by Gabriela Pérez Noriega, the person who more than anybody else has cared for Esteban Volkov and looked after his health and well-being for the last years of his life.

The death of Esteban Volkov signifies the disappearance of the last remaining physical link with Leon Trotsky. But it by no means signifies the end of the struggle that Trotsky began, and to whose continuation Esteban Volkov contributed in no small way. It is the proud claim of the International Marxist Tendency that we are the continuers of this great revolutionary tradition, and we pledge ourselves, over the grave of Esteban Volkov, to continue this fight to the very end.

It is unfortunate that this sad news reached me while on holiday in a house in a small village in the south of Spain where I lack the most elementary means of writing anything serious. I do not have at my disposal either a computer or my notes about the life and works of Esteban Volkov, which remain in a drawer in my office in London. I am grateful to the assistance of a comrade who has had the patience and devotion to copy down my words dictated over the telephone. But I promise that as soon as I return to London, I will write something that will do justice to the memory of my dear friend and comrade Sieva Volkov.

In the meantime, finally, I leave the last word to a Greek poet who expresses my feelings in this sad moment, far more effectively than anything I could write:

They told me, Heraclitus, they told me you were dead,

They brought me bitter news to hear and bitter tears to shed.

I wept as I remembered how often you and I

Had tired the sun with talking and sent him down the sky.

And now that thou art lying, my dear old Carian guest,

A handful of grey ashes, long, long ago at rest,

Still are thy pleasant voices, thy nightingales, awake;

For Death, he taketh all away, but them he cannot take.