Generated by the author using DALL-E-2

The year is 2018. At the prestigious Christie’s fine art auction in New York City, a blurry portrait of a besuited gentleman hangs alongside an Andy Warhol print and a bronze sculpture by Roy Lichtenstein. It is titled: ‘Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy’. An anonymous phone bidder purchases the portrait for a whopping $432,500, against an initial estimate of $7,000-$10,000. At the bottom of the frame, rather than a signature, there is a line of code. It was not produced by human hands, but by an artificial intelligence (AI).

The AI in question is the property of Paris-based creative studio ‘Obvious’, though it was heavily based on open-source software designed by 19-year-old programmer Robbie Barrat. Billed as ‘the future’ by Obvious and the press, this watershed sale set the tone for a debate over AI-generated art that has raged ever since.

With generative AIs reaching new levels of sophistication, some people declare they ought to be thought of as artists in their own right. This includes tech enthusiasts (not coincidentally, a similar crowd to evangelists for cryptocurrency and NFTs, with which AI art is now being combined), along with a growing number of art critics and academics. And as the above example demonstrates, there are buyers willing to pay over the odds for the latest digital craze. Additionally, a number of big companies have already invested billions in capturing this burgeoning new market.

By contrast, many artists complain that machines are ripping off their work, without credit or pay, and fear being rendered obsolete. They baulk at AIs competing on ground that, up until now, had been regarded as the sole preserve of human beings. A 2022 viral tweet by the artist Genel Jumalon, commenting on an AI-generated artwork taking gold at a Colorado State Fair competition, captured this mood:

“TL;DR — Someone entered an art competition with an AI-generated piece and won the first prize. Yeah that’s pretty fucking shitty.”

This year, the famed Australian musician Nick Cave reacted with disgust to lyrics produced by the chatbot ChatGPT in his style:

“Suffice to say, I do not feel… enthusiasm around this technology,” he wrote. “As it moves us toward a utopian future, maybe, or our total destruction. Who can possibly say which? Judging by this song ‘in the style of Nick Cave’ though, it doesn’t look good… The apocalypse is well on its way. This song sucks.”

Despite this harsh review, it is undeniable that the rapid advancement of generative AIs is quite impressive (or alarming, depending on your point of view). But Marxists should take a sober approach to what are, ultimately, merely tools. We understand that all new values are a product of physical or mental labour, carried out by conscious human beings.

These AIs simply churn out images based on the manmade art that we feed them. You get the best results out of them by giving them a prompt appended with: “…in the style of (e.g.) Van Gogh”. They are imitators, not innovators. And without humans creating art, they would have nothing to copy. Moreover, art is not simply an agglomeration of images, sounds, etc. but also the product of lived experiences and social relations, in which machines cannot participate.

That being said, the hostility towards these technologies reflects the fact that machines, which should liberate humanity from toil, under capitalism instead crush both workers and the petty bourgeoisie. In the hands of exploitative bosses, they force people out of employment, and submit human experience and ingenuity to the monotonous rhythm of capitalist production. It can feel as though they dominate us, rather than the other way around. As Karl Marx writes in a brilliant fragment from the Grundrisse:

“Not as with the instrument, which the worker animates and makes into his organ with his skill and strength, and whose handling therefore depends on his virtuosity. Rather, it is the machine which possesses skill and strength in place of the worker, is itself the virtuoso, with a soul of its own in the mechanical laws acting through it… The worker’s activity, reduced to a mere abstraction of activity, is determined and regulated on all sides by the movement of the machinery, and not the opposite.”

Artificial artists?

Experiments with computer-generated art go back decades, but a number of breakthroughs have advanced the field in the last decade. In 2014 came Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which involve a pair of neural networks competing with one another to produce images that best fit the request. This is the technology that produced ‘Edmond de Belamy’. More recent platforms like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 are powered by diffusion models: neural networks that are trained to reverse engineer new images out of Gaussian noise, based on a massive database of existing images scraped from the internet.

Source: fair use

A system called CLIP combines these AIs with natural language prompts. This means a user can type in a word or phrase (for example ‘yellow rubber bath duck’) and the AI will try to create an accurate picture of a bath duck that is not a direct copy of any existing image. This makes them widely usable without any programming knowledge. The more they are used, the better they become.

And these are only the AIs trained to generate images (which will be the focus of the present article). The latest iteration of ChatGPT can produce fairly convincing imitations of natural writing, even mimicking the style of specific authors or publications. In other words, these technologies are becoming more powerful and versatile every single day, to the extent that some proponents believe they have crossed the rubicon into genuine creativity.

For instance, Ahmed Elgammal argues in American Scientist that the Artificial Intelligence Creative Adversarial Network (AICAN), developed by his lab at Rutgers University, should be “thought of as a nearly autonomous artist.” Having been trained on “80,000 images that represent the Western art canon over the previous five centuries” (which Elgammal likens to “taking an art history survey course”), the algorithm deliberately avoids trying to replicate any existing style, with more abstract results than the ‘realistic’ images that GANs are typically used for.

Elgammal argues that people “genuinely like AICAN’s work”, that it can’t be distinguished from that of human artists, and one piece even fetched $16,000 at an auction. This kind of big sale perhaps explains why Elgammal is eager to promote his invention as an “autonomous artist”.

While there is no accounting for taste, Elgammal’s boasts don’t mean very much. Because AICAN produces very abstract images, it’s easy to imagine audiences believing its work is man made. In 1964, critics raved about the abstract expressionist paintings of Pierre Brassau… who turned out to be a chimpanzee named Peter. Moreover, people being willing to pay top dollar for a novelty is no proof of artistic merit, as the recent craze for hideous NFT ‘art’ attests.

Nevertheless, Elgammal and Marian Mazzon, in a 2019 article for Arts, state that although “machine learning and AI cannot replicate the lived experience of a human being”, and therefore “is not able to create art in the same way that human artists do… a different process of creation does not disqualify the results of the process as a viable work of art” (our emphasis).

Similarly, a 2021 paper by Mingyong Cheng argues that, while AI-generated art “lacks the emotional intent found in humans… it is viable to regard creativity based on recent AI technologies” (our emphasis). Her criteria for creativity is making something “unpredictable”, based on a “combination of varied and existing concepts which were never brought together by someone else.”

All these academics have done is move the goalposts for defining creativity. One could attach a paintbrush to a robot arm, programme it to move according to a randomised toolpath, and let it decorate a canvas. The result would certainly be unpredictable, but nobody would describe it as ‘creative’.

Machines do not combine ideas from their training sets in the same way as humans draw on influences from other artists, or their experience of the world, to make new works of art. Elgammal and Mazzon actually admit this in their paper, stating: “[the reason] the machine makes art is intrinsically different [to human beings]; its motivation is that of being tasked with the problem of making art, and its intention is to fulfil that task” (our emphasis).

In other words, AIs are not consciously combining concepts in novel ways according to their own desires. They are algorithmically optimising a task, following a prompt from a human operator, in order to imitate the creative process. They are “brilliant but brainless mimics”, as it was put by Melanie Mitchell, an AI specialist at the Santa Fe Institute.

The emergence of aesthetic sense

In reality, “lived experience” and “emotional intent” are not secondary, as Cheng, Elgammal and Mazzon imply, but fundamental features of creativity. They are defining characteristics of the human condition, and a product of our society.

Generated by the author using DALL-E-2

The emergence of art was an important milestone in the development of our consciousness, and helps to differentiate us from other animals. As Alan Woods explains, “one of the first serious indications of the emergence of our species, homo sapiens sapiens, is the existence of art, that is to say in a concrete expression of aesthetic sense.”

The upright posture, and adaptation of our hands for tool use – for labour – gave mankind access to additional nutrition, which facilitated the development of our brains. These two factors, the hand and the brain, were instrumental in developing the germ of art, which emerged out of productive activity, long before class society. A number of studies suggest that some of the very earliest stone tools created by anatomically modern humans are ‘over-worked’ for form (particularly symmetry) beyond the strictly functional.

This is not yet art, but the primordial beginnings of art, which subsequently evolved over time. Other hominids like homo erectus and homo neanderthalensis might also have expressed an aesthetic sense, but only homo sapiens developed this into full-fledged art. The earliest possible example is the so-called ‘Venus of Berekhat Ram’, which has been proposed as a crude carving of a woman, which dates to around 250,000 years ago. From these humble beginnings, all art and culture eventually sprung. To quote Engels from ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’:

“Only by labour, by adaptation to ever new operations, through the inheritance of muscles, ligaments, and, over longer periods of time, bones that had undergone special development and the ever-renewed employment of this inherited finesse in new, more and more complicated operations, have given the human hand the high degree of perfection required to conjure into being the pictures of a Raphael, the statues of a Thorwaldsen, the music of a Paganini.”

In other words, the early aesthetic sense was a product of the development of the human body and mind through labour, laying the basis for art to emerge. The purpose of technology, when used for artistic ends – from the paintbrush to the printing press – is to extend the capabilities of human beings, who are the original and sole source of artistic creativity. Machines are not in themselves creative. A digital camera can produce a very detailed image instantly, but everybody recognises the photographer behind it as the real artist.

Unlike machines, humans are spontaneously driven to produce art. A two-year-old, with no artistic training, left in a house unsupervised for an hour will begin to scribble on the walls. This innate inspiration can then be cultivated through education, and the mastering of technique in adulthood. But you could give the most advanced AI access to billions of images for inspiration, then leave it undisturbed for 1,000 years, and it would never produce so much as a stick-figure doodle: let alone invent impressionism, or compose a symphony.

But why did art develop? What is its purpose? Alan Woods argues that, at root, it is basically a peculiar form of communication. Leon Trotsky names art a “form of cognising the world not as a system of laws [as with science], but as a grouping of images and, at the same time, as a means of inspiring certain feelings and moods.” This is another unique quality of art that is beyond the comprehension of machines. AIs can create images, but the shared emotional experiences, “feelings and moods” communicated through art are of another order entirely.

For instance, Pablo Picasso’s ‘blue period’ – in which his colour palette and subject matter became notably dark and sombre – was inspired in part by the suicide of his friend Carles Casagemas in 1901. An AI perceives Picasso’s art merely as an assortment of shapes, colours and defined values. It can imitate the look of these works, but cannot grasp the emotions that inspired them. You could ask an AI to make a ‘sad’ image, but even if it produced pictures in dark colours of people crying, it wouldn’t understand the content of sadness, because it has never been sad, nor happy; nor has it experienced any other feeling.

Furthermore, art is a social phenomenon. Each generation participates in developing both technique and ideas, teaching a new generation, and raising all forms of culture to new heights. And of course, art develops in tandem with the class struggle. Without the emergence of the bourgeoisie in the 16th-17th century, looking back to the great artistic and scientific works of antiquity to rail against the stifling influence of feudalism and the Church, there would have been no Renaissance. The triumphant, discordant phrases of Beethoven’s Eroica were forged in the aftermath of the French Revolution. The films of Ken Loach are a direct product of capitalist exploitation in postwar Britain. Machines cannot participate in society or the class struggle, and have no understanding of the history or context behind the images they produce. All of this prevents them from being truly creative.

The limits of AI

It is actually quite a simple matter to illustrate the limitations of generative AIs as compared with human artists. A 2022 study at Cornell University found that DALL-E 2 consistently failed to illustrate both simple spatial relations between objects (e.g. ‘X on Y’), or abstract relations between objects and agents (e.g. ‘X helping Y’). In fact, participants in the study felt the AI’s output matched their prompts only 22 percent of the time. For example, it could reliably generate a picture of “a spoon in a cup”, but the prompt “a cup in a spoon” just led to more pictures of spoons in cups. This is because the image training set contained many spoons in cups, but no cups in spoons. The AI interpreted these terms on a surface level, without understanding the individual components or their relationships between them.

Generated by the author using DALL-E-2

I performed a few experiments of my own with DALL-E 2 for this article, the results of which lined up with the Cornell study. For example, the prompt: “a horse with an arrow pointing at one of its legs”, resulted in pictures of horses with arrows near, next to and around them, but not pointing at their legs. The AI understood ‘horse’ and ‘arrow’, but could not extrapolate legs from the picture of the horse, nor put the arrow in relation to them.

Even the most artistically challenged human could probably do a reasonable job of my request, because we are able to think abstractly and dialectically, seeing parts in relation to the whole. But, as the Cornell researchers conclude:

“Even with the occasional ambiguity, the current quantitative gap between what DALL-E 2 produces and what people accept as a reasonable depiction of very simple relations is enough to suggest a qualitative gap between what DALL-E 2 has learned, and what even infants seem to already know.”

And this is a key point. An infant knows these simple relations because they experience them in the world, through their senses, which a machine lacks. A baby learns what is hard and soft, what is hot and cold, by interacting with objects – picking them up, feeling them, and making generalisations based on this experience. For this task, the least-developed and least-experienced human is more adept than the most-advanced AI.

I further put the DALL-E 2’s creativity to the test by asking it to generate an image of “an animal that does not exist and nobody has ever seen before.” One could imagine a small child using this prompt as an opportunity to draw something really fantastical: with tentacles, 12 eyes, feathers and a duck’s bill. The AI gave me a picture of a hippopotamus, a capybara and a monkey. It is organically incapable of generating original ideas.

Generated by the author using DALL-E-2

AIs face other stumbling blocks as well, which illustrate the sheer complexity of operations a human mind is capable of. For one thing, they cannot cope with prompts longer than about the length of a tweet. Also, while AI is now quite good at producing static images, written text (albeit short passages) and short videos, it struggles with artforms that unfold over longer periods of time, like music. Attempts by programmes like OpenAI Jukebox to imitate the style of popular artists, like the Beatles for example, require a lot of tweaking by a human being to be remotely passable. Their ‘original compositions’ fall apart into an unlistable, incoherent mess after only a few seconds. For now, at least, Sir Paul McCartney can rest at ease.

Part of the problem is subjectivity is immensely complicated, and while AI might improve on the basis of technological development, it is more than just a question of computational power. Human beings are very adept at telling when a piece of music, or an image, is ‘off’. But this is very hard to quantify in the way a machine can fathom.

This also explains the nightmarish quality of many AI-generated images, in which people have 12 fingers on each hand and other bodily deformities. Such distortions are a byproduct of the AI mashing together thousands of images it doesn’t actually comprehend. These features are wrong, but the AI has no way of intuitively knowing what is right.

Replacing human artists?

While generative AIs are not truly creative, and they still have a long way to go even in copying manmade art, there are some applications for which they are already ‘good enough’. A number of tech companies use AIs to produce basic web copy, and image processing platforms like Photoshop utilise AI for image correction. One Russian commercial design firm used an AI system (under the pseudonym Nikolay Ironov) that had been trained on hand-drawn vector images to develop ‘original’ designs.

It is telling that AIs are most applicable to some of the least ‘creative’ tasks in the media industry. They have also proved popular for sleazy purposes, as attested by the thriving subculture of AI pornography ‘enthusiasts’ and the increasing use of AI to create ‘deep fakes’, in which a person’s face can be overlaid on pornographic content (or anything else besides).

Aside from these seedy applications, AI is now competent enough at generating images and text that working artists are starting to regard them, not as “artistic collaborators” – as Cheng hopes – but unwelcome competition. Writer for the Atlantic, Charlie Warzel, found himself at the centre of a twitter storm last year after running an edition of the magazine’s newsletter with a picture of conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, generated by the AI Midjourney. Many commercial illustrators were furious that a prestigious gig was handed to a neural net. Cartoonist Matt Bors commented:

“It’s not like there’s a ton of illustration happening online… Go to a website and most of the image content is hosted elsewhere. Articles are full of embedded tweets or Instagram posts or stock photography. The bottom came out of illustration a while ago, but AI art does seem like a thing that will devalue art in the long run.”

Other artists have objected to the plagiaristic tendencies of generative AI. A Google search for Polish artist Greg Rutkowski will produce thousands of images he never created, because his style is very popular among AI art enthusiasts. And the law provides no protection for working artists. In 2022, the US Copyright Office affirmed that it cannot enforce copyright over AI-generated art, because artworks are “the fruits of intellectual labour… founded in the creative powers of the [human] mind.” On this point, we actually agree! However, under capitalism, where artists’ original styles are a part of their market value, this is a problem for individual creatives, and beneficial to the bosses and wealthy speculators.

The Design and Artists Copyright Society (DACS), which collects payments on behalf of artists for the use of their images, states: “There are no safeguards for artists […] to be able to identify works in databases that are being used and opt out”. As a result, Jon Juárez, an artist who has worked at prestigious game studios like Square Enix and Microsoft, worries that AIs could potentially serve as “washing machines of intellectual property.” He states: “If a large company sees an image or an idea that can be useful to them, they just have to enter it into the system and obtain mimetic results in seconds, they will not need to pay the artist for that image.”

Concept artists in the film, TV and video game sector have complained that AI will soon force them out of the market, or at best transform them into mere ‘supervisors’ for machines. Bruce (not his real name), an artist who has worked on a award-winning indie games, says in Kotaku:

“The endgame of a potential employer is not to make my job easier, it’s to replace me, or to reduce all my years spent honing my craft into a boring-ass machine learning pilot, where I’m trained to vaguely direct an equivalent software in hundreds of different directions until by chance it spits out an asset we could feasibly use in a game… I could easily envision a scenario where using AI a single artist or art director could take the place of 5-10 entry level artists.”

The potential of AI to replace human artists with machines (who do not command a wage for their work) is not lost on capitalists in the tech sector. It is no accident that the most powerful generative AI technologies are owned by the likes of Google (Imagen), Meta (Make-A-Scene) and Elon Musk (DALL-E 2). These fatcats don’t care a jot for whether the art made by AI is good, just whether it can be used to cut costs and increase their profits. This encapsulates the philistine attitude of the capitalists, who have no interest in art and culture unless it can be exploited in some way. They place no value whatsoever on the time, care and pride artists invest into developing their craft. On the contrary, this just makes them more expensive to hire.

Already, working artists face a market where their work is underappreciated or underpaid – if they are even paid at all! Commercial artists are so often expected to work for free that the phrase ‘paid in exposure’ has become a running joke in the industry. In this context, it is no surprise that AI, which can produce huge quantities of work without demanding a wage, is treated with suspicion.

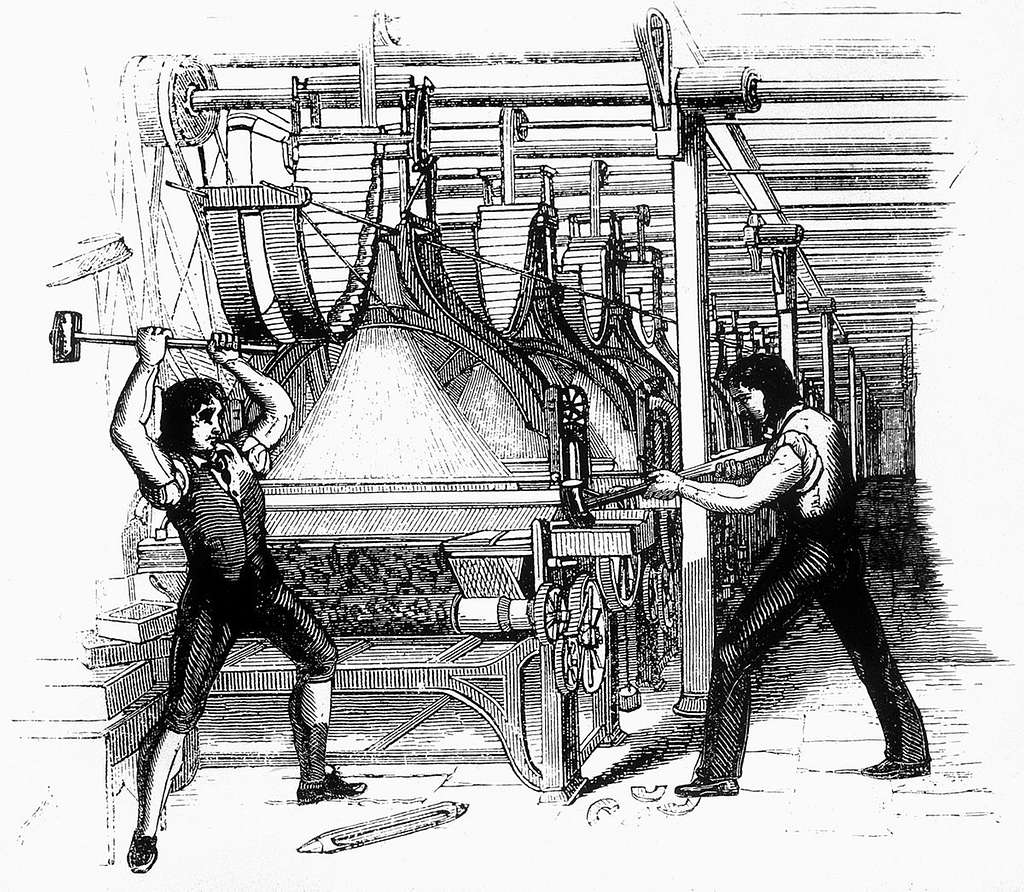

Under capitalism, the function of machines is to put more productive power at the elbow of fewer workers, cheapening commodities to undercut the competition and increase profits. A consequence of this is that unemployment goes up, and skilled labour is increasingly replaced by unskilled labour. Artists and writers fear a future in which, if they can get work at all, they merely ‘tweak’ the output of machines, for a lower fee than their currently specialised skill set commands. In the past, the march of capitalist development replaced artisans making commodities by hand with fleets of workers operating industrial machinery in factories. Today, AI and automation are undermining middle-class professions as well. A January 2023 article in the Atlantic, titled ‘How ChatGPT Will Destabilize White-Collar Work’, states:

“In the next five years, it is likely that AI will begin to reduce employment for college-educated workers. As the technology continues to advance, it will be able to perform tasks that were previously thought to require a high level of education and skill. This could lead to a displacement of workers in certain industries, as companies look to cut costs by automating processes.”

The relentless march of capital forces all working layers of society to become mere appendages of machines, or face the scrapheap. As Marx explains:

“The section of the working class thus rendered superfluous by machinery, i.e. converted into a part of the population no longer directly necessary for the self-valorisation of capital, either goes under in the unequal context between the old handicraft and manufacturing production and the new machine production, or else floods all the more easily accessible branches of industry, swamps the labour-market, and makes the prices of labour-power fall below its value… [the machine] produces chronic misery among the workers who compete with it.”

The anger over AIs today contains echoes of the Luddite movement in the 19th Century. This saw workers, who had been thrown into the hell of early industrial production and alienated from the products of their labour, turning their anger on the machines that embodied their chronic misery. In reality, the capitalist system was responsible for turning the great accomplishments of industry into fetters on the human body and spirit. Today, new technologies are subjecting sections of the intelligentsia to similar pressure, and provoking similar animosity between man and machine.

Could AI be a force for good?

Under a democratically planned socialist society, machinery, automation and AI would free humanity from dull and dangerous tasks. The kind of ‘mutually beneficial relationship’ that some talk about today could only really exist in a society where these technologies are not privately owned by capitalist corporations; one in which unemployment and concerns over copyright are consigned to the dustbin of history, along with the regime of private property itself, meaning artists would be free to create and share their work as they wish.

There are lots of potential benefits to generative AIs. These tools have the capacity to save a great deal of time: serving as a digital sounding board, to rapidly iterate on ideas. They could also handle basic design tasks, like coming up with the fabric print on the seats of public transport, for instance; or generating dull and purely functional copy, like public information messages and instructional pamphlets. This would free up human minds and hands for higher forms of creativity.

Moreover, they could enhance the existing arts. They are already used for tasks like film restoration, programming and certain photo editing processes. AI could be used to increase the depth, accuracy and complexity of all the visual arts: rendering texture, shadow and sunlight in minute detail in an instant, freeing up human beings for composition and innovation.

Every new creative technology (from polyphonic instruments to photography) carries the potential to extend humanity’s abilities, raise our sights and open new artistic opportunities. However, capitalism today is at an impasse, and has dragged culture into a rut. Fully exploiting the benefits of AI would require rational planning, rather than anarchic profit production, under which it results in the displacement of labour, lower living standards for workers and the middle classes, and the homogenisation of culture. It is no accident that anxiety over AI is rising at a time during which the deepening crisis of capitalism is immiserating not only the working class, but increasingly the middle classes as well.

AI has not transcended humanity, and (despite the reservations of Nick Cave) it need not doom us. But under capitalism, it might make our lives and culture worse. Freeing culture from the dead hand of capital is a revolutionary task, which can only be accomplished by the working class. Ultimately, once class society has been abolished, art will cease to be a plaything of the rich, or a commodity to be exploited for profit. It will belong to the whole of humanity, and make full use of our technological advancements to reach unknown heights.