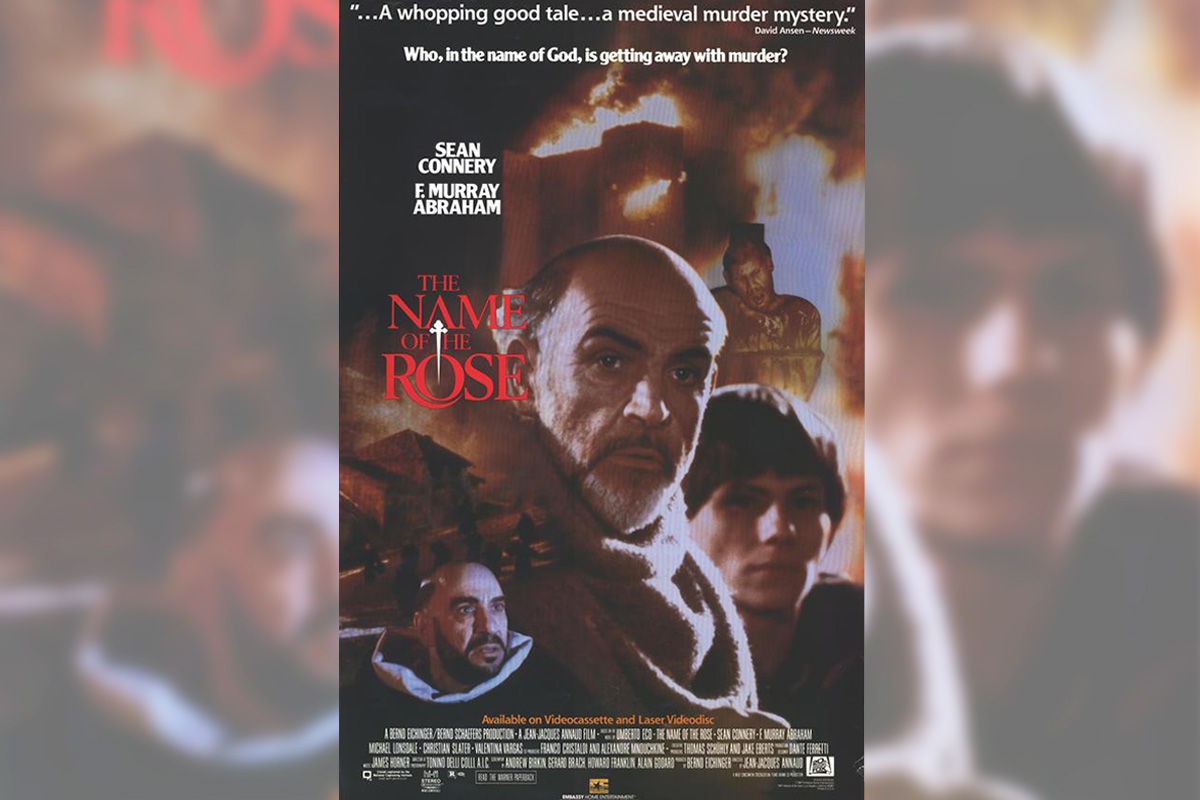

The Name of the Rose (1986) is a powerful polemic against religious obscurantism and in favor of reason. But for us communists, this film, based on Umberto Ecco’s novel of the same name, is also an attack on philosophical idealism and a plea for materialism.

The plot of Jean-Jacques Annaud’s film takes the form of an investigation into a series of mysterious deaths in a Benedictine abbey in 14th-century Italy. The deaths occur at a time when an important theological congress is to be held there between Franciscans and papal representatives. One of the Franciscan representatives, Friar William of Baskerville (Sean Connery), and his young protégé Adso of Melk (Christian Slater), set out to investigate.

The abbey’s leaders insist that these deaths must be the work of the devil. Baskerville, a scholar and admirer of Aristotle, believes that the causes should be sought in the material world, using reason before resorting to the supernatural.

As the investigation progresses, Franciscan delegates and papal representatives arrive for their debate. The Franciscans, who have taken vows of poverty, rail against the crass luxury of the Church. They argue that Christ himself was poor. The Pope’s representative, engulfed in his flamboyant vestments, asserts that the debate “is not whether Christ himself was poor, but whether the Church should be.” Needless to say, he has no intention of abandoning his obscene wealth in the name of religious principles.

The source of all this wealth is well illustrated when we see the poor peasants lining up to hand over their offerings. The contrast between the extravagant gilding of the abbey and the high clergy, and the abject poverty of the peasants is striking.

When a representative of the Inquisition arrives, he quickly finds three easy scapegoats as the source of the diabolical infiltration: a woman, a feeble-minded hunchback, and a former Dolcinian. The Dolcinians were a radical sect calling for a return to the primitive communist roots of Christianity, considered heretical. All the clergy, except Baskerville and his protégé, rally behind this idealistic explanation.

But Baskerville discovers why the abbey’s senior administrators clung so tightly to these superstitions: they preferred it to uncovering the truth. This Benedictine abbey has a rich library, and its monks devote themselves to preserving and transcribing ancient texts, as well as translating them. The discovery of an ancient text lies behind the murders. Some high-ranking members of the abbey consider it dangerous for the Catholic Church, and are prepared to do anything to prevent it being translated and distributed.

The Name of the Rose invites us to beware of those who reject reason and who seek to obscure reality with idealistic explanations. Reason and the search for an objective explanation for phenomena in the material world are dangerous for the rich and powerful, because they shed light on their crimes. The Church’s influence is greatly diminished today. But it is postmodern philosophy, which also denies the possibility of science and an objective understanding of the world, that dominates intellectual life. Who’s afraid of reason?